the Indian Ocean is the smallest, therefore, the most unpredictable (due to the closely surrounding continents.) And she didn’t let her image of being the most feared of all oceans be tarnished this time, either.

On September 12, the 20-25 knots Easterly wind slowly died. And while the barometer took a dive, it started backing to NNW.

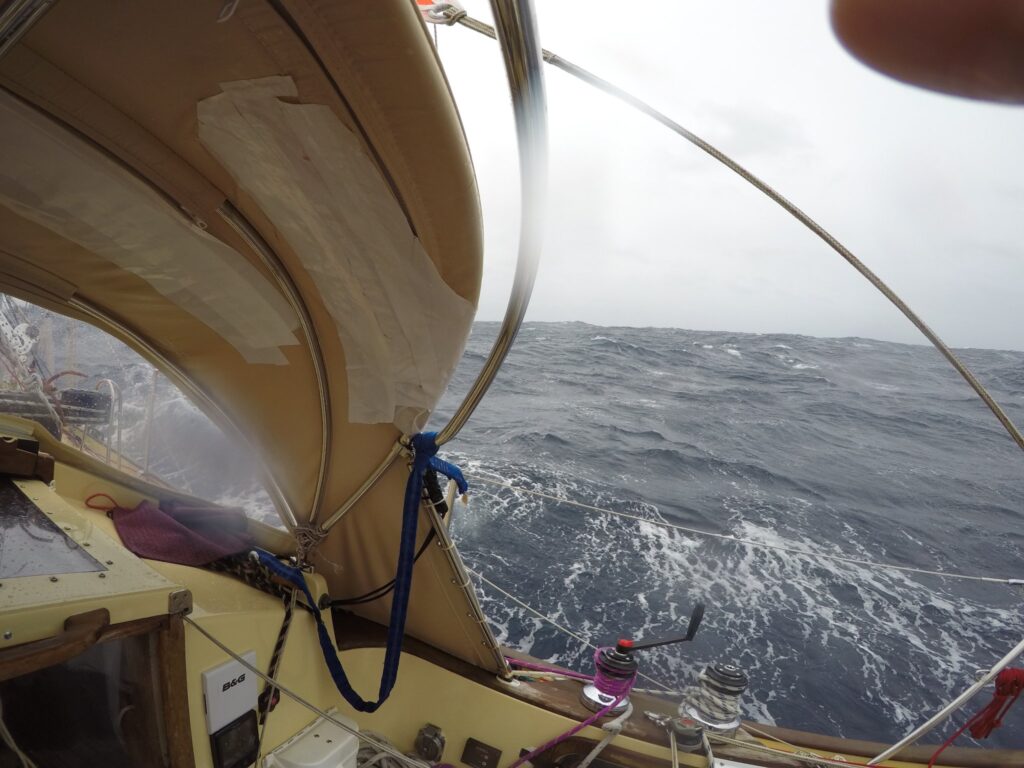

It was blowing 45 knots by the next day, building matching seas and soaking Puffin thoroughly.

There was nothing unusual here, at the 41 South latitude.

The surprise came on the 15th, during the night. The wind weakened and backed further to SSW so I could put a spinnaker boom on the Yankee.

The sky cleared up with only occasional lightning in the distance, so I took a short nap in my bunk.

Puffin’s sudden heel woke me up. A sharp metal bang followed it while I was racing to the cockpit.

It was too late to act; I was just in time to witness the sliced-up Yankee.

Puffin lost her Yankee as the sheet snapped in an unexpected blow

A 50-knot blow, like a magical Jeanie from a bottle, erupted from the, literally, blue sky. It snapped the jib sheet and ripped the Yankee into pieces, all while banging the spinnaker boom into the Selden furling.

The Yankee is a favored offshore headsail, mainly on reach, because the high-cut clew keeps the sail out of the waves.

I had replaced the far bigger, low-cut Genoa with this Yankee just before entering the Southern Atlantic due to the prevailing wind and for safety. I had enjoyed its performance very much, but, unfortunately, not for too long.

One of the special features of Puffin is the double inner stays

Sailing in the foggy English Channel is never boring

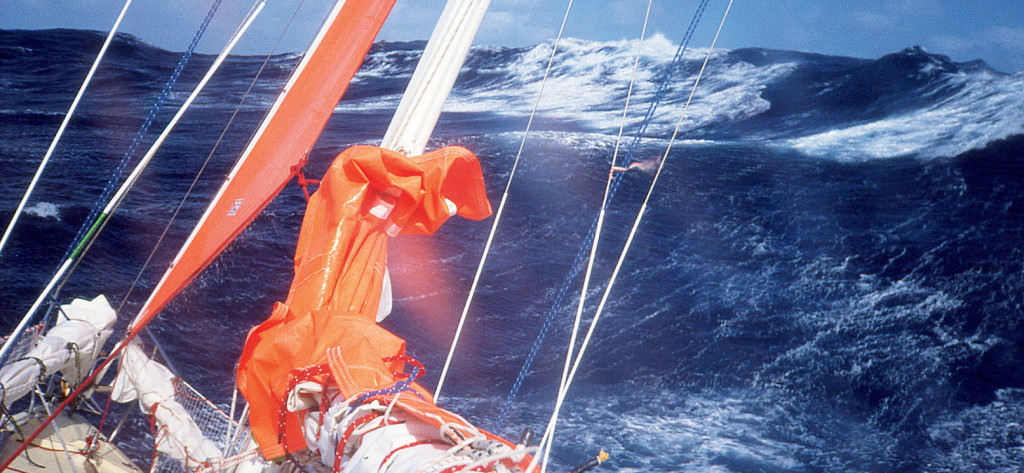

On September 17th, the Easterly wind (as a reminder, we were sailing in the Westerlies) forced Puffin into upwind sailing. Later Puffin was forced to “heave to” as the wind was backing and growing into a 55-65 knots NNW-ly storm.

It is prudent to slow down the boat to reduce the wear on her hull and rig—and for safety.

When running in conditions like these, or even on a broad reach, we might want to tow a long loop of heavy lines or any drag-creating objects (tires, Bruce anchor, etc.) to prevent broaching.

A supportive sailor buddy of mine worked for weeks on a self-made Jordan drogue, a long series of little parachutes. He shipped this bulky and heavy thing to New York. And despite having never used such a thing, I wedged it into the already overloaded Puffin as a token of appreciation for his hard work.

On September 18th , the storm muscled up to 65 knots and promised a good testing opportunity for this donation, so I deployed it. But the storm calmed down by the evening, and the test was unsuccessful only due to its short duration.

I turned to the North on the 19th to avoid the center of an approaching new storm, and with that move, the point of sail was almost downwind.

I am not a fan of downwind sailing. It is the slowest and most dangerous course, especially for solo sailors who do not have an autopilot or are not permitted to use an autopilot (like in this race).

Downwind sailing is the birthplace of accidental jibes and broaching, which might be followed by knockdowns (or even pitchpole capsizes) in heavy weather.

I did capsize (luckily, not pitchpoling) on this ocean. I was further eastbound and at higher latitude. This was back on November 17th, 1990. I’ve tried to avoid downwind sailing in storms since then.

Nice try sail ride

Salammbo-my 1st solo circumnavigator boat- is in the Indian Ocean, 1990

The wind veered to SW and increased to 35-40 knots by the morning of September 20th, and we kept the Northerly heading with reefed sails on a broad reach. The sea got rough, but the wind vane kept Puffin on course, so I left it alone while making breakfast below in the galley.

The cockpit was dry, and I had to reach out to the propane tank to open it, so I did not close the companionway completely, leaving the upper washboard off.

Well, it was a huge mistake!

A rogue wave hit Puffin. She was knocked down on her right side, landing me on the chart table—with an escorting waterfall.

The 4-ton keel righted the flooded boat relatively quickly, helping my recovery, too.

I cleared myself from the stripped shower curtain, which worked as a spray hood around the chart table. Then I switched the electric bilge pump to manual since the auto mode did nothing, despite the cabin getting flooded with seawater above the floorboard.

I raced to the manual bilge pump behind the steering wheel and started my unscheduled workout.

The 75-liter per minute maximum capacity of the Henderson MK5 manual pump must be brochure data only. I was still pumping water after an hour of constant pumping (the estimated volume of the water intrusion in the cabin was 250-300 liters).

I tried to measure the outside damage while laboring at the pump. The mast looked all right; just the foldable mast steps opened on the starboard side. The hanks broke off the staysail, leaving a loose luff flip-flopping wildly around the inner stay.

Most of the cockpit inventory landed in the cabin. Just one rope bag and winch handle diverted to the sea. But the damage on the spray hood was significant. Its canvas got torn up in two places, and the stainless frame got a weird bend.

The real trouble waiting for me was inside the boat.

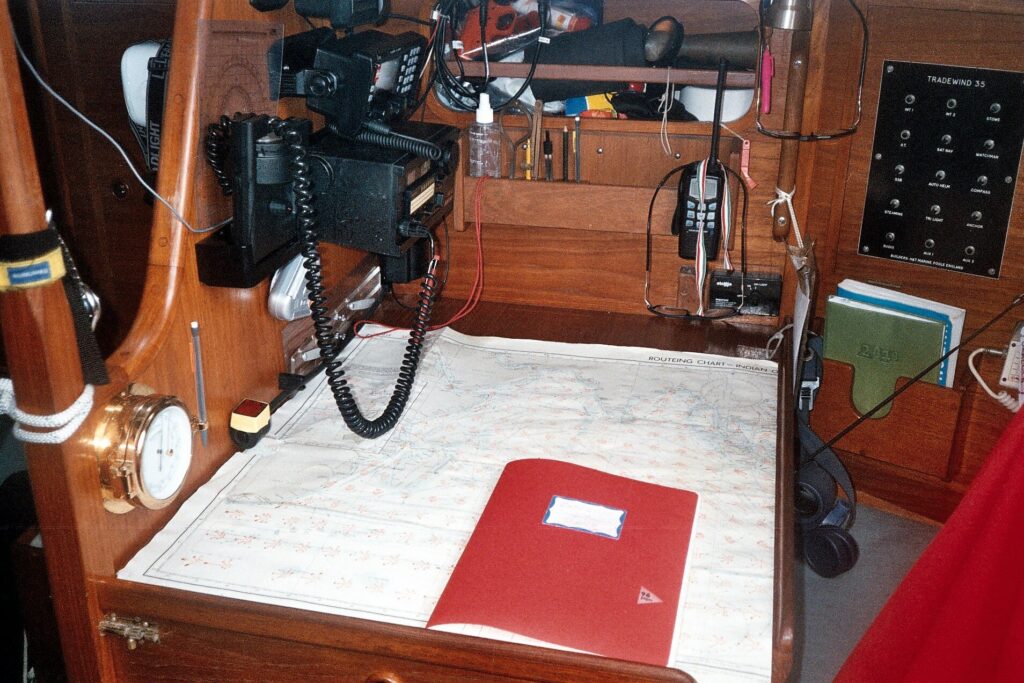

Almost everything on the starboard side was completely flooded, including batteries, charging regulators, gauges, the inverter, VHF and HF radios, radio beacon finder, AM/FM radio/cassette player, nautical charts, books, my logbook, the chart table and seat—and my bunk, including my sleeping bag and pillow—were soaked.

Even after I pumped out most of the invading seawater.

I learned later all my pumping was unassisted because the electric bilge pump could not work due to the flooded battery compartment.

Everything looked bad, but surprisingly, the condition of my bunk bothered me the most (I have never had a desire for a water bed). This was a weird but clear sign of my frustration, reflecting an unconscious desire to escape into a deep sleep.

The dodger canvas got ripped

The chart table before the knock down

The chart table after the knock down

The bilge after its pump out

But there was no time(or place) for sleep. So, I put Puffin into “heave to”. My number one risk management task was to minimize the electric damage.

I had to empty all the flooded compartments and remove the trapped water. I started with the battery storage, obviously. Luckily, I could rescue the batteries, but all their attachments (regulator, monitoring gauges) became defective.

The next two days, I worked feverishly to restore what I could while Puffin crawled painfully slow at 2-3 knots.

The flooded VHF was not repairable, and I had to replace it with Puffin’s original VHF from 1986. I took apart and cleaned the HF radio several times. In the end, I could only restore the last frequency used— and on the receiving side only. From now on, I was the only competitor in the race without operable radio.

The inverter, the radio direction finder, the depth sounder, and the AM/FM radio-cassette player were inoperable, becoming literal dead weight as did my unique collection of 100 cassette tapes.

But everything is relative, and I could not complain about my trouble. I learned this later, from Don, during our mandatory satellite connection; both Abilash and Greg were drifting dismasted.

On September 23rd , I took off Puffin’s shackles and speeded up while staying on the 36 S latitude for a warmer, smoother ride. I was also hoping to dry out my charts, sleeping bag, clothes, and Puffin’s interior in general.

We did increase our speed but not for long, as the features of the Horse Latitudes are similar everywhere, including the Indian Ocean.

We got trapped in a calm on September 25th, and fixing the damaged dodger became the next item on my work order.

The spray hood (or dodger) had two functions on board of Puffin; besides shielding the companionway from spray, it was an essential grab bar.

All the lines (halyards and reef lines) were at Puffin’s mast; they were not led back to the cockpit. So I used the spray hood frame frequently to keep me in balance while moving back and forth during reefing/jibing (runners).

Plus, it supported me while I was shooting the Sun or Moon with my sextant.

This support collapsed during the knockdown; the stretched canvas was ripped, and the frame was damaged.

Its repair was imperative for my safety, and the calm weather gave me the opportunity. The dry, sunny weather and Puffin’s seamanlike inventory were helpful in the job. But fixing the damaged frame required real creativity—above regular seamanship.

During the constant manual steering—thanks to the unreliable wheel adaptor—I kept my eyes on the damaged frame long enough to find the right solution.

The eye-end of the left frame pipe got bent 90 degrees when the freak wave hit it. This fitting was a solid, one-piece stainless steel piece with no spare on board.

I could not risk trying to straighten it in the vise; there was a good chance of breaking it. So, instead, I installed a turnbuckle on the rear bulkhead of the cabin and angled the pulling force equally on the bent fitting with three different sizes of shackles. This allowed me to straighten it gradually without breakage while tightening the rigging screw slowly.

The frame got its original shape back and tensioned the patched canvas perfectly.

My genius system, which I left in place, also provided additional support and a safer framework. I patted myself on the shoulder and attached my favorite survival knife to the savior rigging screw as a reward.

I did feel much better and got an additional boost from a curious whale family which swam around Puffin a couple of times, almost pushing us towards the racecourse.

The friendly sea mammals’ cheering seemed a good omen because we could continue our voyage in a fresh 20-30 knots northerly breeze.

The HF radio got blind and isolated us from the outside world

and patch the ripped canvas...

The best tool to reshape the bent dodger frame was a uniquely fitted turnbuckle

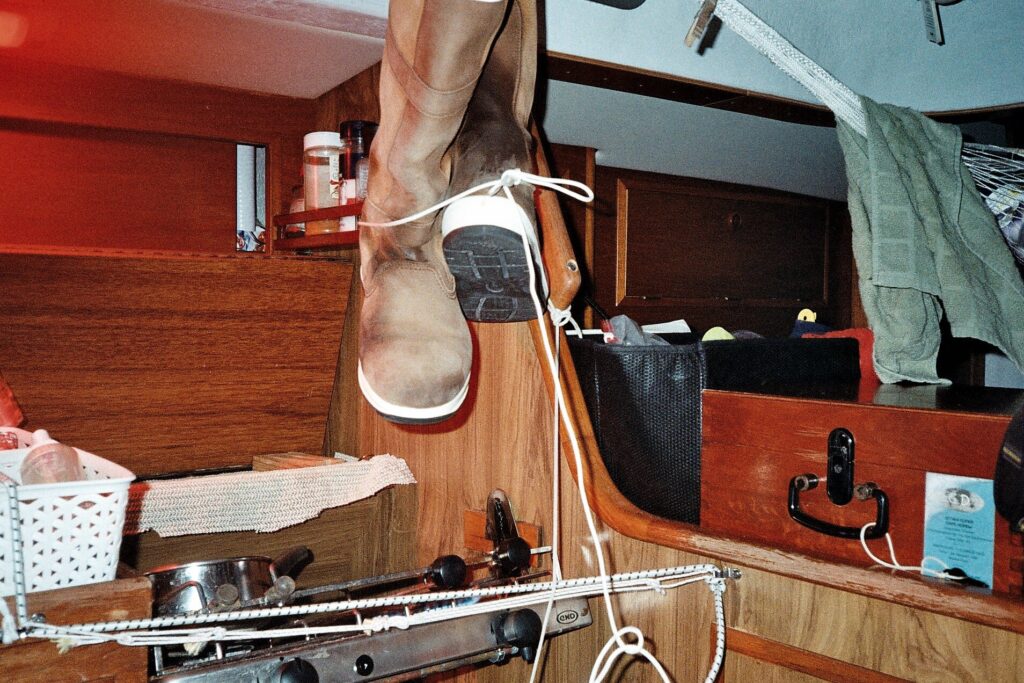

The boots could be dried above the stove

But we had to sail to lower latitudes to dry out the soaked charts

The friendly whales directed me back to the race

and gear...

I could seal the interior, again and head to higher latitudes

But luck favored Kjell Litwin (a Swedish sailor) even more; I learned later he was really short on drinking water (he was down to one liter by the time we arrived).

Kjell departed from Falmouth with the GGR competitors for his solo circumnavigation but was out of the race.

He lost his drinking water somehow (a water tank leakage, probably) and alerted GGR’s race management for help. Don asked me if I could share some water with Kjell, as I was the closest to Selene, his boat.

We had our short date on September 27th, when I delivered twenty liters of water in a flexible plastic tank via a heaving line attached to a securing life jacket. Kjell wanted to return these items and perhaps spend more time together, but I rushed back to the race and left the stuff behind.

My decision proved extremely helpful when any delay in my arrival at the shelter anchorage in Tasmania might have caused serious problems.

The following day, Almighty rewarded me with a good shower. And for the first time after three months, I could collect some rainwater. But the Windex—on the top of the mast—which might have been damaged during the knockdown, became completely frozen.

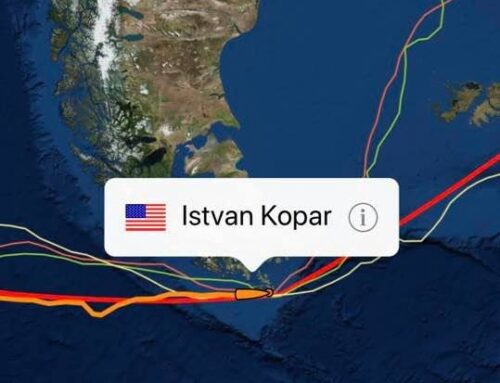

September 30th marked the end of the fifth month when Puffin and I left Oyster Bay, New York, so we sailed one month more than the other competitors in the race.

And after our knockdown, like Sir Robin in 1968, we sailed alone and isolated without operable HF radio, radio direction finder, depth sounder, or reliable wind vane—but we kept pushing further on.

Accordingly, the month of October felt much longer than the previous ones. All the while, Puffin was inching from 36 S to 44 S latitude along her constantly curving track shaped by the storms. The timing of the storms for the weekends and calms for the weekdays has become the routine.

We passed Amsterdam Island on October 5th and the second ill-famed Cape, Cape Leeuwin, on October 20th —the last one in another serious storm.

We barely avoided a second knockdown, but I modified the classical “heave to” for a more productive “heave to to go” keeping Puffin close to her desired heading with more speed.

In the meantime, Puffin’s inventory shrank further with losing the second spare rotator on Puffin’s Walker log, so my dead reckoning literally became dead; that is, highly estimated, due to a lack of measuring the covered miles.

And the icing on the cake was the deterioration of my health by the spreading mold in Puffin’s interior—just one more by-product of the capsize. The mold occupied everything inside the cabin; then, it traveled to my nails and my lungs. My immune system weakened, and one of my teeth got inflamed.

Closing in on our mandatory checkpoint in Tasmania, I was faced with the dilemma of whether to see a dentist and move into the Chichester class…again.

To be continued…

Puffin & I were in good hands...

But mold started to invade everything on board...

After the sail bags the wood got molded

The corrosion showed up after the mold