November greeted Puffin above Tasmania’s continental shelf—and almost on the rocks of Maatsuyker Islands.

A strong storm was Tasmania-bound. Don urged me to accelerate my progress, hoping for better shelter in the coastal area.

I would have rather slowed down, as the open waters offer more safety for solo sailors. And I hate any coastal approach in a rush. But assuming his reasons were good enough for his hint, followed his suggestion.

The shortest distance to the D’Entrecasteaux channel led through the Maatsuyker Islands. These consist of half a dozen islands and several rocks that are not quite island-size.

Sailing solo among them—based only on estimated position, in the dark, and in heavy weather— looked like a nightmare. And, indeed, it became a real one. This leg qualified as the riskiest part of my entire race.

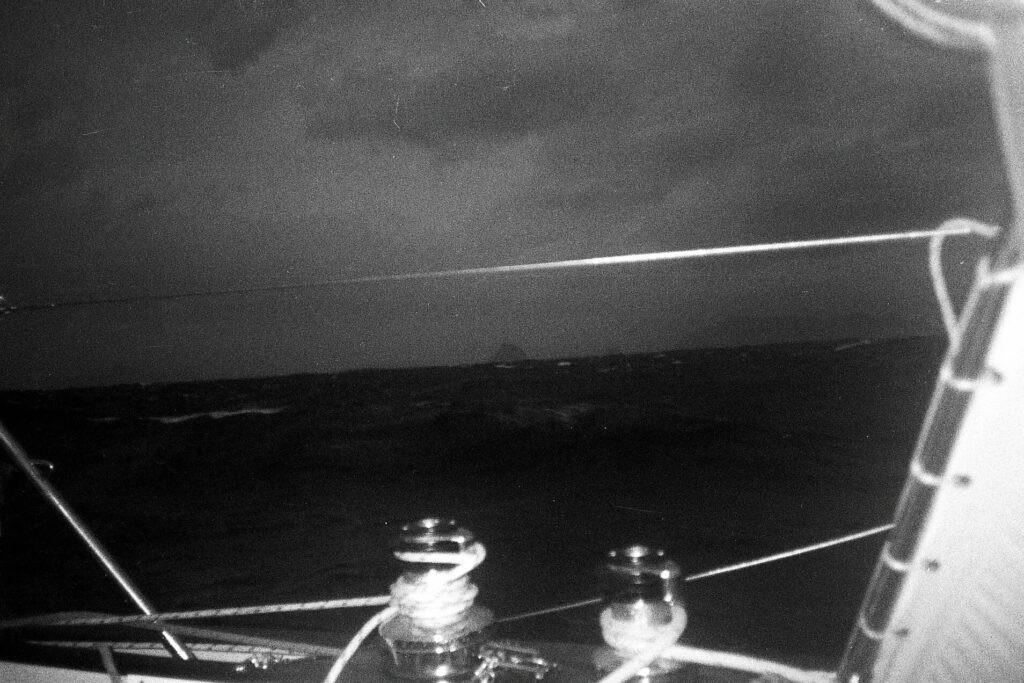

The rocks behind us became visible just at twilight

Sailing blind among the unlit rocks

Puffin & I sailed blind through those rocks during the night

I could not take bearings of the only lighthouse (the Southernmost lighthouse of Tasmania is on Maatsuyker island) in the desired intervals to get my position because of the unreliable wheel adapter. It kept me glued to manual steering in the nasty weather.

It was nerve-racking—blind sailing among the hidden rocks which could end our race and probably our life simultaneously. Almighty’s guardianship became obvious at dawn when the contours of these steep-sided, dark monsters became visible behind Puffin.

But we had to reach a safe shelter before the storm’s peak. And it was possible with a shortcut via the D’Entrecasteaux channel, inside of Bruny Island.

Further Heavenly assistance was in high demand as the storm got stronger, and me less so. The sea became shallow with scattered reefs, so I switched to storm sails. I did this to avoid a speedy grounding because I did not have an operable depth sounder (it was broken in the knockdown).

Recherche Bay looked like a suitable shelter, and I saw a boat already anchored there. But my upwind maneuvers to get inside that bay were unsuccessful. My storm sails, ideal for offshore heavy weather sailing, failed me in the close-hauled upwind sailing as the wind frequently shifted in direction and strength.

I had to keep going in the still wide but reef-divided channel, relying only on my biosensors. The next charted prospective anchorage was Southport, in the Bay of Deephole. Puffin had to race against the approaching dusk and the storm’s peak.

I started the engine to improve Puffin’s control, but the undersized prop (beneficial during offshore sailing) did not help much, and my upwind sailing into the bay failed—again.

Completely frustrated, I kept sailing further into the darkening channel. After analyzing my options, I decided to make a risky move. I sailed eerily close to the peninsula on the bay’s East side, then changed tack and hugged the shore, just an arm-stretch distance from shore, while sailing towards the anchorage.

The nearby land and vegetation weakened the wind and frequently gave a favorable lift for our heading. But it also threatened us with nasty grounding.

Sheltering in Southport Deephole Bay

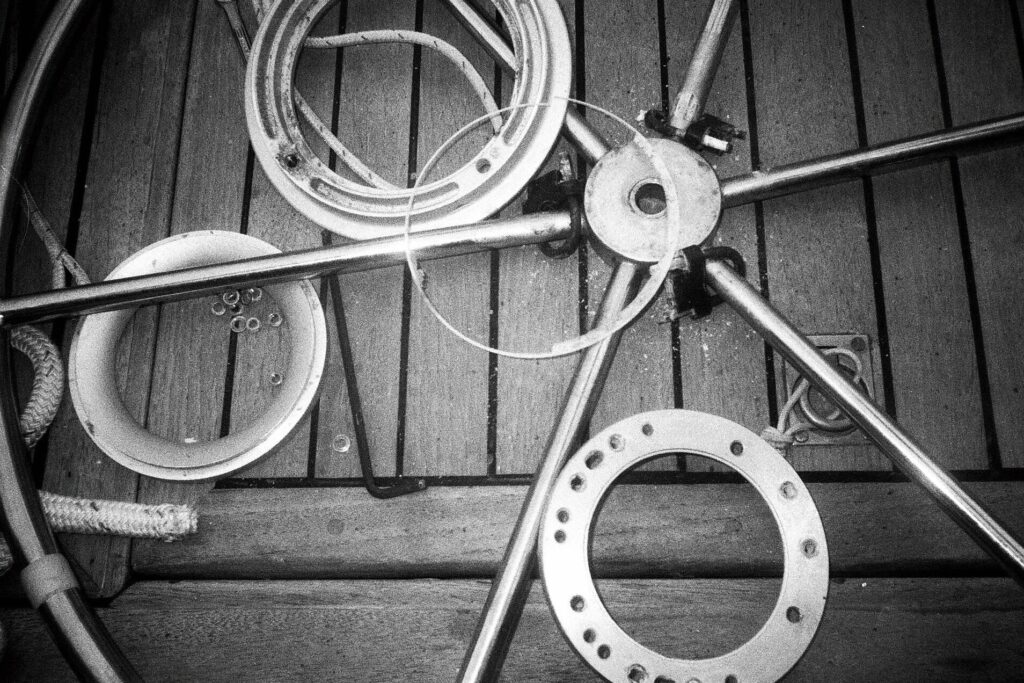

Rebuilding our regular troublemaker

The white Delrin rings got jammed and paralyzed Puffin’s steering

Mr. Murphy could not pass up the opportunity and picked the best time for a surprise breakdown. This time Windpilot’s wheel adapter did not slide but got jammed during the next tack—completely locking up Puffin’s main steering.

I quickly untied the wind vane’s control lines, but I still got chained to manual steering—again reducing my coastal navigation to pure guessing. Miraculously, Puffin reached the anchorage safely. And, with God’s final boost, I secured her by the peak of the storm.

It was early evening, November 2nd, and I was completely drained from the nonstop struggle of the last two days. I crashed into my bunk, hoping for an undisturbed, long sleep.

But it wasn’t to be.

Muscle cramps caused by the constant physical load and dehydration woke me up frequently and hurt like hell. In pain, I screamed while crawling to the galley to mix another magnesium drink—luckily, I was not heard on shore. The storm quickly swallowed my cries—it’s no accident that the nearby landmark is named “Roaring Beach.”

The following day was no quieter. My pain-caused screams morphed into frustrated cursing after I took apart the wheel adapter, the Windpilot’s main troublemaker.

The Delrin insert rings got wrinkled and jammed together the separate discs as if they had been welded—paralyzing our steering and endangering our life. I got really mad this time and changed Murphy’s name to Peter for the time being.

Hobart bound in d’Entrecasteaux Channel

The black & white photo killed the lush green of the gorgeous surrounding

Smooth sailing finally Hobart bound

Moving forward, I got Puffin shipshape after the repair. The voyage continued in the beautiful D’Entrecasteaux channel, heading N-NE, Hobart bound.

My eyes, fed up with four long months of ocean monotony, hungrily gulped the varied scenery and lush colors of the surrounding landscape and its vegetation. The heaven-like environment and the welcoming greetings from shore put the bad memories of recent months into exile surprisingly quickly.

I was euphoric, indeed, seeing the approaching boat flying the GGR flag as we entered the estuary of River Derwen.

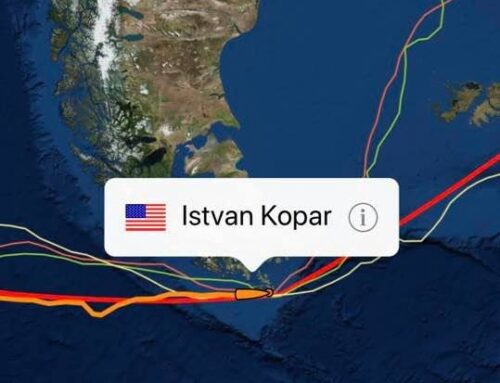

Puffin’s shortcut to Hobart

Heading to Hobart check point

Entering to Hobart check point

I recognized Don and Jane. And to my surprise, Yannick & Aida were also on the crowded boat; they flew over from France just to welcome Susie and me.

The two boats rafted after anchoring. The crew executed the most unusual yet welcome greeting to keep with the GGR race rules, which allowed no physical contact. And, as another unforgettable surprise, Jane called my wife via her I-pad. I could see and talk to Eva—all while Jane was leaning overboard with outstretched arms like a champion athlete.

This checkpoint event in Hobart and the French finish became the most valuable moments of my Golden Globe Race. Only six skippers, including Sir Robin, were gifted this way.

But at this time, the finish in Les Sables d’Olonne was still doubtful and far away, so I decided to stay at the checkpoint for the night and continue the race after a well-deserved rest.

Aida, Don and Yannick are in the front to welcome us

Hobart check point

I departed on November 4th under a gorgeous sunrise, waving goodbye to Don and Jesse, GGR’s filmmaker, whose drone escorted Puffin for a short distance. I tried to smile into the camera of my flying follower despite the bad memories of its first appearance.

Ah, see, there is no joy without bitterness, and it proved true during the Hobart visit, too…

The boats ahead of me left their drag behind during their short stop in Tasmania. But the locals in Hobart, after learning about this process, forbid barnacle removal to protect the biosphere of the river estuary.

Hitchhiking barnacles slow down sailboats significantly or increase fuel consumption on commercial ships. I wanted to clean Puffin’s bottom while we were sheltered at Deephole Bay. I was just jumping in the water with my scraping tools when a drone showed up and started to circle above Puffin.

I aborted the bottom cleaning as the drone’s mission was unclear. I learned its reasons later, just after my arrival to Hobart; Don had directed Jesse’s drone to Puffin’s shelter for film shooting. I got pretty upset about this “friendly fire” that Don did not alert me to in advance.

Puffin and I would have been much happier to leave our drag-inducing barnacles behind instead of some video footage.

To be continued…

Made it to Hobart…