The gorgeous Tasmanian coastline faded, and we lost view of land by November 5th. We hoped to see land again at Christmas, with some luck at Cape Horn.

Friendly sailing alongside Tasmanian shores….

Farewell Tasmania…

We were not even mid-way to the finish, but I was raring to go like a stable-bound horse.

Well, perhaps I should not dare to compare myself to a horse—but to a donkey, staying in the race despite the ongoing technical breakdowns. I also had to take care of my cart (Puffin).

There is no use quoting more land-based analogies as everything is completely different on the oceans.

The daily routine, for example, does not start in the morning.

The demand to adjust the sails and the course is at the mercy of the weather but maintaining a constant lookout for traffic or shore is even more crucial to avoid a collision or running aground.

So, the biggest challenge for the solo skipper is to create the proper routine and adjust it to the current region and weather.

The solo sailor must constantly be on alert in main shipping lanes with heavy commercial traffic, near land, or in shallow water. Yet, they cannot drain their energy either.

The solution is maintaining a cautious balance in resting, eating, dressing, and relaxing. The solo sailor must learn to rest with “cat naps” and go to sleep depending on the current conditions.

I, for example, prefer to sleep for longer periods during the daytime when my boat is more visible to other vessels.

This allows me to spend more time on the deck during the night to avoid potentially being overrun by commercial ships (small sailboats usually reflect very weak radar signals, and the lookout on cargo vessels is far less disciplined nowadays).

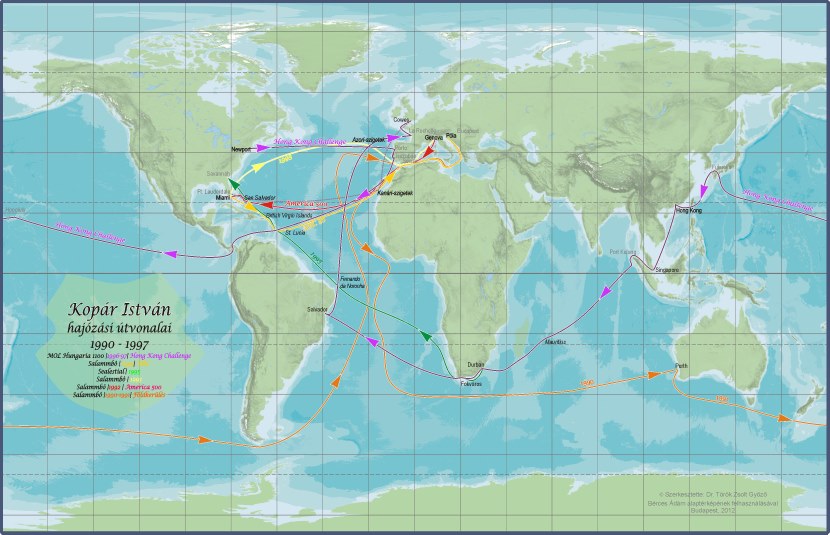

Navigation is the solo skipper’s other main priority—especially in Golden Globe Race, where no GPS or other electronics are allowed.

The easiest celestial bodies to shoot in small boats are the Sun & Moon due to the constant pitching and rolling. But they are often covered by clouds as the weather frequently changes in the Southern Oceans. The skipper should be on sharp standby and ready to shoot the Sun or Moon whenever they show up.

I did paint all my solo, offshore boats orange to be visible...

My living space for almost a year….

Major tools of celestial navigation

A sort of predictable routine might be maintained in the Trade Winds or in steady storms. These are the periods when the sailor can spend more time caring for himself and his boat.

Surprisingly, the calms are challenging for maintaining a regular routine.

The lack of wind does not mean a calm sea offshore. Swells are still rolling the boat, chafing sails and lines, and causing more damage than storms. There’s a lot of frustration with little progress.

So, life at sea is very different. But creating the proper routine (based on weather, region, traffic, etc.) is still very important.

I prefer to maintain personal hygiene (including shaving), reading, and listening to radio stations to stay in touch with civilization. And I am constantly focusing on boat maintenance, keeping Puffin seaworthy and ready for emergencies.

However, I spent far less time caring for myself in this race.

My budget limited the proper race prep, equipment supply, and provisioning.

There was no money for the desired wind vane (self-steering device), which is very important in single-handed sailing where Autopilot is not allowed. I got stuck frequently at the steering wheel for endless hours of manual steering and spent several days heaved to for repair work.

Maintaining the daily routine is a piece of cake in the Trades

Sighting is fun this time…

Getting in & out with the sextant in one hand is not easy in rough weather

My first solo circumnavigation was similar to the current one since I navigated by celestial navigation and was completely unassisted. But that time, I stopped once. It was for four weeks in Fremantle, WA.

There was not much fun on that trip until Australia, as it was my first solo offshore endeavor, and I lacked the related experience. But my Aries wind vane was super reliable, and after my stopover, I started to enjoy single-handed sailing, having learned its tricks.

My first single-handed circumnavigation was a real solo accomplishment because I did not use AIS, a radar transponder, a satellite phone, or a YB tracker. This equipment is currently assisting the competitors in the GGR. And previously, I could not rely on my fellow competitors either.

But on that trip, my Aries wind vane was super reliable, and after 4-5 months of solo sailing, I started to enjoy it. I crossed the Pacific Ocean by setting up daily records while having fun (in the range of 180 nm/day with a 31’ lake design sloop).

So, I was expecting a relatively fast ocean crossing this time, too, despite my current technical issues.

But it did not happen that way for two reasons.

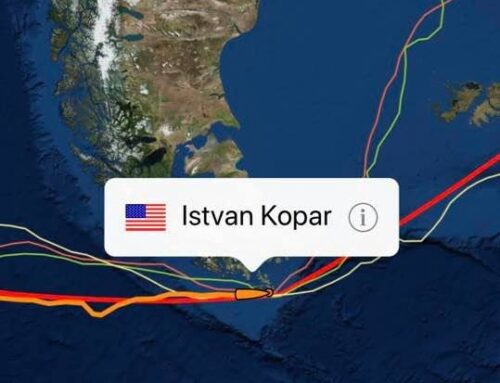

In 1990-91, I could choose my routing on my own, and after rounding Tasmania, I sailed the shortest distance towards Cape Horn, changing my course by the ice alerts only.

During my 1st solo (one stop) circumnavigation I was able to pick my own routing

Salammbo (Balaton 31') Cape Horn bound, in 1991

We had to obey the GGR “No Go Zone” rules this time. The rules created detours in the hope of safety (The “No Go Zone” was established between and below 46°S, 174°W, and 46 S, 115 W).

The other reason Puffin slowed down was the Windpilot itself jeopardizing the boat’s main steering—in addition to its constantly failing wheel adapter.

The new problem showed up after rounding New Zealand, which meant life on board Puffin was never boring.

One way to secure the troublemaker

Walker log got its poor replacement after loosing its propeller

Without steering wheel, again

A lively tracker behind Puffin

Calms and thunderstorms were alternating each other between Tasmania and New Zealand, causing confused seas frequently. The weather was unusually warm considering 46th latitudes, which helped to progress the mold infestation on board.

Perhaps unrelated to these conditions, I had to replace more light bulbs both in the compasses and cabin lights and fight with Puffin’s stubborn hitchhikers, the barnacles.

The only good news came on November 10th from Jean-Luc; he did not abandon the race as he was able to fix his damaged mast after the capsize.

On November 12, we passed South-West Cape, the Southernmost point of Stewart Island, New Zealand, leaving only the ill-famed Cape Horn unchecked (of the five Southernmost Capes).

Puffin was already at the 48th South latitude, but I had to change our heading towards lower latitudes to obey the “No go zone.” Unfortunately, this meant a longer distance to sail and much slower progress due to lighter winds and frequent calms.

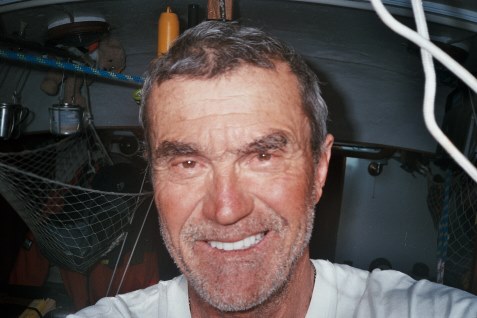

Half way done smile…

The other setback came when we left New Zealand behind.

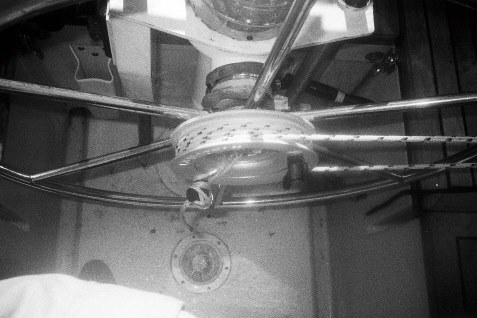

Puffin’s original steering system is a Whitlock Cobra 4, where the steering wheel moves a push rod via cogwheels to move the rudder instead of cables. This way, the helming becomes more sensitive and direct (just like steering with a tiller).

I like this system for its reliability, too.

I had Whitlock Cobra 5 steering system during my first solo circumnavigation and had no issues, even after two Atlantic crossings. But my wind vane was an Aries, not a Windpilot at that time.

The Windpilot performs better than the Aries in a light breeze, on a broad reach, or downwind (when the apparent wind is weaker).

The Windpilot’s control lines are shorter and have less friction due to its more direct transmission to the steering wheel (a brilliant engineering shortcut from Peter). But for the very same reason, the waves’ impact conveyed to the steering wheel is less dampened.

The Whitlock Cobra 4 or 5 Pedestal wheel steering has rigid contact everywhere. The cogwheels and pushrod cannot absorb the vibration or the shocks transferred by the more sensitive Windpilot the way cables can. So, the steering wheel shaft bearing receives the full impact.

I took apart everything on Puffin during her restoration, including the Whitlock pedestal, which I serviced properly. (See Puffin’s restoration on my website.) There was no play on the bearing, even at the race start—after my Atlantic crossing.

Windpilot on Puffin

Aries wind vane on Salammbo

But by now, my steering wheel was wobbling like an unbalanced cart wheel. I had to push it forward to keep the cog wheels engaged, which meant constant manual steering for me.

Well, on November 20th, I looked at the charts for the nearest islands as I ran out of drinking water, and my steering wheel was acting stoned drunk…

To be continued…

But 37 was my lucky number...