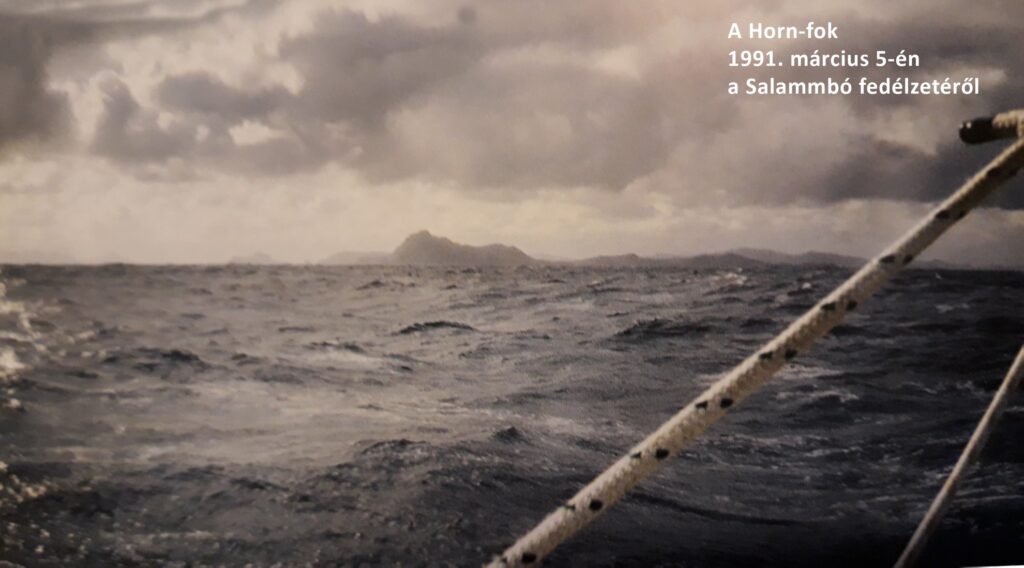

My father and friends cheered for me remotely while I rounded Cape Horn for the first time back on March 5th, 1991.

This time two of my friends, and my father, were close by. Not virtually, but, unfortunately, in a rather tangible way.

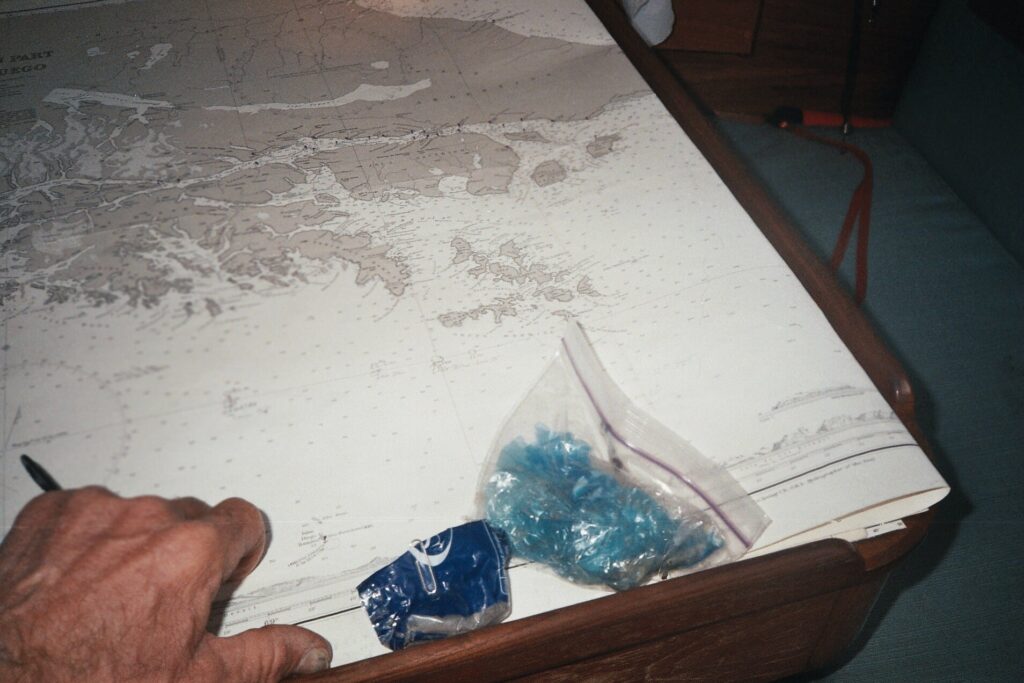

My father’s ashes and a handful of soil from Dezso Balogh and Jeno Szitnyai’s gravesites traveled with me on board Puffin to this final destination. And, now, I could spread them into the water of their admired geographical location.

I, however, saved a small urn of my father’s ashes till the end of the circumnavigation so I could return it to his birthplace, in Hungary. My plan was to spread his leftover circumnavigator ashes into Lake Balaton, at Keszthely, his birthplace, from the deck of M/V Helka, his favorite ship. (I executed this plan after the race in May of 2019.)

These were very emotional minutes onboard Puffin. Humbled deeply by their never-fading connection and togetherness and this unique farewell.

Hungarian soil from my friends’ graveyard will be spreaded into ocean at Cape Horn

This urn with my Dad’s ashes will be launched at Cape Horn

But Puffin shifted into an unexpected acceleration pushed by a strong current and reminded me of my skipper’s tasks.

And the Windpilot’s wheel adapter got jammed—again—while we were speeding with 9-10 knots towards the ill-famed Straits Lemaire.

The wind beefed up, above 35 knots, but I could not leave the steering wheel to reef the main. I made my second irrational decision in the race and left Puffin surf-like gliding in this scary strait. (The first was the stormy night sailing among the unlit islands of Tasmania)

We were balancing on a blade edge, stretching my nerves to their break points, but Puffin, her solid Selden rig, and Peter Sander’s well-made sails did not let me down. And with some Upper Assistance, we left this danger zone behind in one piece.

I did not dare to come this way in 1991. Instead, I rounded the Falkland Islands from the East.

But we were in a race now, and my only choice was to do the opposite of what Uku did if I wanted to catch his faster boat.

Cape Horn for the 1st time with Salammbo March 5th, 1991

Cape Horn bound with Puffin January 1st, 2019

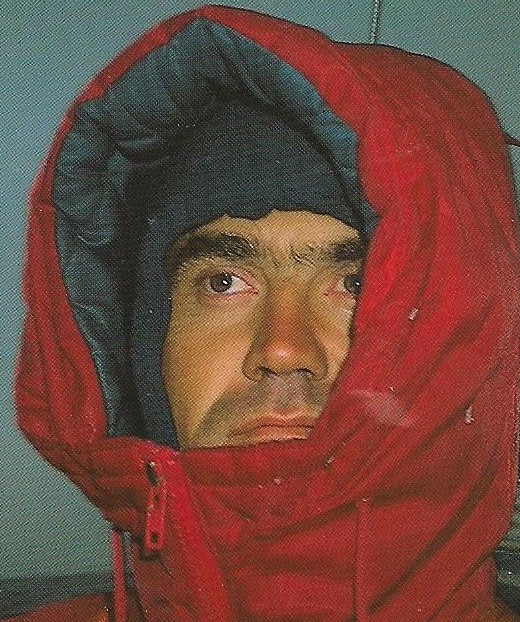

1st time at Cape Horn, March 5th,1991

Cape Horn January 1st, 2019

John Wood's (US Wellness Meats) Pemmican kept me energized in the Southern latitudes

Party is on the horizon, the French Champaign and the fruit cake from Sir Robin will be consumed after the rounding…

There she is…

The 1st Cape Horn check in for Puffin, the 2nd one for me

She is ahead of us, finally

Yes, it was a rational decision, but it resulted in very unpleasant sailing.

Frequently changing winds and confused sea made good progress difficult, and one time we were completely blocked by the most unusual wave trap I have ever seen.

The shapeless monsters born of the wind and currents’ sudden changes attacked Puffin from bow and stern simultaneously, putting her to a writhing halt.

“This was my life’s most unusual sea state, hell on the sea itself,” made the note in Puffin’s logbook on January 9th, 2019.

Theoretically, the cold Falkland current would have propelled Puffin toward the goal line, but the unpredictable Malvinas current intervened and built serious speed bumps.

However, this was just icing on frustration’s cake. Its filling has always been the constant sabotage of the Windpilot’s wheel adapter.

On January 17th, we sailed into a strong counter-current, most probably the warm Brazil current, because I could not see Puffin’s bowsprit in the fog.

My body adjusted to the current conditions and to the final phase of the race, of course.

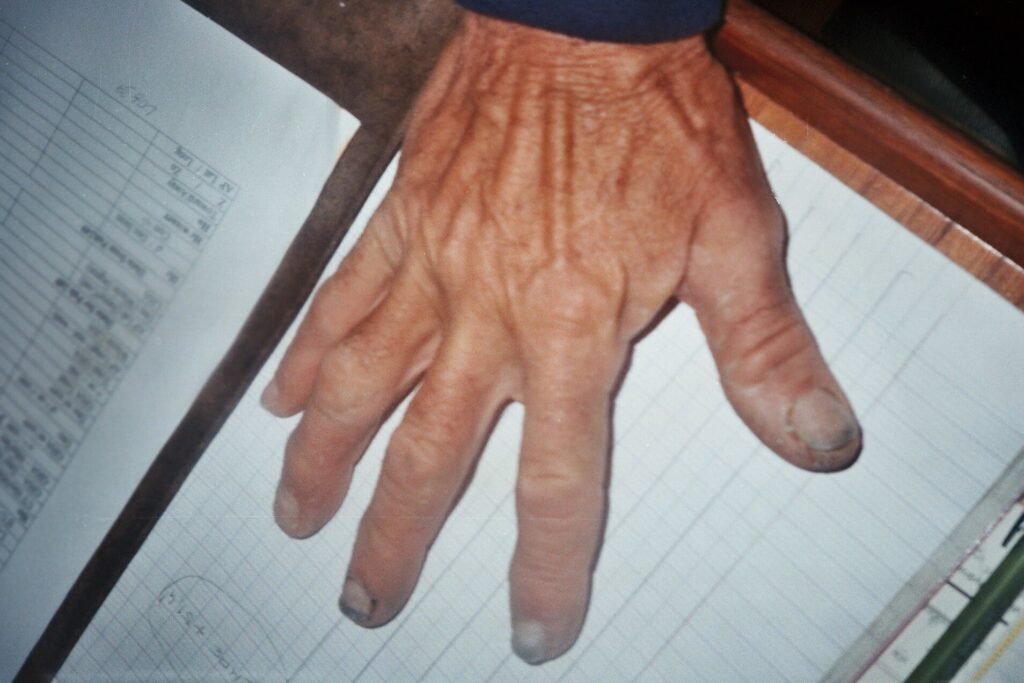

My fungus-infected nails opened up further, my shoulders and knees hurt more frequently, and I broke a rib during a maneuver.

January 19th ranked among the worst days of the race regarding the weather. The wind shifted all around—360 degrees. Its velocity varied between 0 to 55 knots. And by the evening, it became a three-day-long powerful storm with continuous lightning and rain.

The silver lining was the 40 liters of drinking water harvested during this period.

On January 23rd, the sky cleared up, and finally, I could have a thorough bath in the cockpit. Also, I could open the Dorado vents to help reduce the mold infestation growing in Puffin’s interior.

I had to take apart the steering pedestal—again—because my made-up bearing started to fail in its supporting function keeping the cog wheels together.

I decided to use the rebuilt emergency tiller for a while since Puffin was heading towards a more gentle sailing environment.

I wanted to save the far more effective wheel steering for the race’s last leg, where storms and shipping traffic are more frequent.

I shaved my head bald before crossing the Tropic of Capricorn, thanks to the Southern Summer, and maintaining hygiene onboard became much easier.

On January 27th, I shifted Puffin’s steering to the emergency tiller as we got steady south-easterly trades sending the steering wheel for vacation. But the Windpilot wheel adapter would have been sent to some recycling place instead…

Well, the south-easterly trades were light and unsteady, but I was able to exceed the northbound moving Sun by the end of January, at least.

It was great to be in the warm weather after the freezing cold of the Southern Oceans, but as we know, even too much of a good thing can be harmful…and the sun was beaming full throttle.

These days we met merchant ships and even sailboats more frequently.

By February 5th, I shortened Uku’s advantage to 490 nautical miles. However, it was weird to race against the faster Rustler with an emergency tiller.

But it was even more bizarre that Tapio, with a much faster boat, was 3500 nautical miles behind Puffin, which was definitely the slowest boat in the GGR fleet. (Later, I learned that barnacles slowed down Tapio).

The usual dilemma of where to cross the doldrum has always been a challenge. But the heavy displacement boats trapped into wind holes mixed with occasional thunderstorms have little chance for route modification later on.

Winding up my Wempe chronometer daily

The emergency back up drinks were secured under the screwed down floor board to reduce my temptation

On February 9th, we finally crossed the Equator at the West longitude of 30 degrees 48 minutes, and we were now in the same hemisphere as our loved ones.

The trades shifted northeasterly, and we had to sail closehauled from now on, which was not well received for the tired emergency tiller.

On February 16th, I reinforced it with additional through bolts, but its usable end was clearly visible.

On February 21st, I had to go on the mast top again. I installed an outside block with a messenger line in it as a spare to avoid further halyard chafe and another climb.

On March 1st, I tripled the daily intake of Balance of Nature, a fruit and vegetable supplement suggested by Dr. Howard, one of my greatest supporters, to strengthen my immune system and fight against the mold-caused diseases. The recommendation was transferred via Don during our weekly Sat phone dialog.

We were sailing at the latitude of the Canary Islands already, but our finish in France was still in limbo due to our helming issues.

The emergency help was nearby thanks to the busy shipping traffic, but sometimes too close, resulting in potential collision danger—not assistance.

The doubtful return and struggle to catch Uku overwhelmed my body and showed scary signs on March 6th.

My left arm went numb, and the chest pain and shortness of breath made me rush to the yellow pelican case for aspirin. I had to let the race go in my mind and focus only on the finish.

On March 7th, I was in sight of land for the time after Cape Horn—the peak of Pico Island.

On March 8th, an infinite number of dolphins greeted me for my 66th birthday among the Azores. And thanks to God, alive.

The mold infested fingers are visible already, the other symptoms hunted me down after the race

I returned Puffin’s helming to the wheel steering, which made maneuvers easier in the frequently changing weather and in the middle of dense shipping traffic.

This swap was possible through my new technical invention—a freely rotating push rod that kept the cog wheels engaged in the pedestal by pushing the steering wheel forward while the Windpilot was in charge.

I sacrificed a Harken block with ball bearings, installing its sheave onto a fully threaded stainless steel rod where I could adjust the pushing force via washers and nuts.

The push rod was a significant obstacle in the cockpit during the maneuvers. But it gave me relief after lengthy manual steering and made sail changes, navigation, eating, and resting possible.

Early mid-March welcomed us with cold, stormy weather while we sailed towards the ill-famed Bay of Biscay.

On March 14th, the shifty wind forced me into constant manual helming while my ankles were bitten by the cold.

One of my inventions is in action. Home made push rod keeps the cog wheels engaged

The secret ingridients of my latest invention are 1 piece of SS threaded rod, 1 sheave of a ball bearing block, washers & nuts, 1 PVC pipe, 1 marelon pipe fitting and a PVC cone

At this point, the Windpilot did not respond to the wind shifts at all.

This was a completely new deficiency with no reasonable explanation. There was no sign of any damage or broken part. It simply became inoperable.

But there were still 600 miles to go before the finish, so I decided to replace the complete unit with its spare one.

Peter, the inventor and manufacturer of Windpilot, was very proud of many features of his baby. And its easy installation and replacement, even at sea, were among them.

Well, there was no trouble with removing the old one but a lot of hassle with its replacement.

Puffin’s motion was pretty lively even in heave to. But the major problem was the inaccuracy of the connecting fittings. I mentioned Peter’s name—repeatedly—while hanging over the stern under the pushpit rail, washed over by the waves while I had to file the mismatched fitting down, frequently underwater.

But the real “black soup” came after the successful installation when I saw that the pendulum rudder was also a mismatch—it was far too short and obviously made for a smaller boat.

More than half of the pendulum rudder was in the air, even after the adjustment to lower it to its maximum.

I moved all the light stuff to the front of the boat and all the heavy items to the stern to get a deeper bite in the water with the pendulum rudder.

Puffin was sitting on her rear bottom by the time I finished the work. But I was so exhausted I could not even sit on my butt.

To be continued…..