Below is the English version of Part 4. For the Hungarian version, please click here.

Sir Robin shot his gun aboard Suhaili at noon sharp. Puffin crossed the north side of the starting line, in the first quarter of the fleet.

The weather was hot and muggy, in accordance with the season. But the fans did not seem to care. They showed up in big numbers, both on land and out on the water—causing a lot of work for the race organizers who needed to keep them in order. All the entrants appreciated the attention of the crowd, but we were less happy with the wakes of the power-driven boats and the cover of the sail-driven boats that came along with it.

I waved like a lifeless puppet to my wife, who was sitting in one of the escort boats. Both of us were completely exhausted from the overload of the last two weeks, and not even sensing the doubts of seeing each other, again…

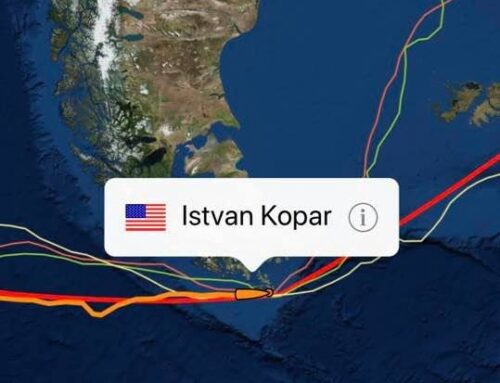

After a couple of hours, the GGR fleet was left alone, and spread out quickly. Philippe Peche’s boat speed was quite outstanding—leaving even the other Rustlers behind as it disappeared beyond the horizon. The ill-famed Bay of Biscay showed its midsummer tranquility. Windless spots were shifting with the light breeze, keeping the water flat and mirrorlike.

My goal was to get to the Portuguese Trades, which were supposed to be blowing steadily along the Iberian coast during the summer. But first I had to clear the Bay of Biscay, which is the size of the Black Sea.

The advantages of faster, lighter boats and the local knowledge of certain skippers (currents, winds) soon became apparent. Puffin, with the company of the other Tradewind (Sagarmatha, Kevin Farebrother’s boat), was quickly left behind.

I was enjoying the slow progress at first, hoping for a well-deserved rest and to catch up with the operation of my untested equipment after being recharged. But it was a short-lived hope, because the Windpilot mechanical wind vane did what it had done before (during my Atlantic crossing), once again forcing me to steer manually. I could not sleep, navigate, get to my radio, or even get to the stove.

The high numbers in my thermometer and barometer, coupled with the low numbers in Puffin’s Walker log, together served to increase my frustration while I was glued to the steering wheel. I became completely isolated from the rest of the fleet, unable to even listen to the radio.

I completely dropped the idea of reinspecting the wind vane since its creator, Peter, had serviced it just a couple of days ago. Everyone can make mistakes, of course, and I should have thought of that. But later on I could not think straight, probably due to my exhausted condition.

Peter made the Windpilot super sensitive by extending the pendulum arm, reducing the friction of control lines by this shortcut

On July 7, I finally got out of the Bay, but fell into a complete lull (windless spot). For the first time in my offshore sailing history, I dropped all the sails, before dropping myself into my bunk for a couple of hours.

I was crawling south, parallel with the Portuguese coast in the 6- to 10-knot winds of the steady high pressure. On one hand I was hoping to get to the Portuguese Trades. And on the other I was looking for the guidance of the coastal lighthouses, due to the overcast sky.

But my coastal navigation put Puffin almost on the rocks while approaching the Burlings (the Berlengas Archipelago). These inhabited islands are north of Lisbon, 10-12 km off the coast. They served as a shipping graveyard in the old days, which I could relate to now, being without modern navigational equipment.

The largest island there, Berlenga Grande, is well lit by its lighthouse. But the surrounding islands/isles are unlit, and the visibility is often extremely poor here (due to the summer sea fog), making my pulse beat fast…

I had last sailed in this area in 1996—from Porto to Lisbon. But that time I had been with a dozen-man crew, GPS, and detailed charts on board of Hungaria 1100 (Tripp 55’) in the Hong Kong Challenge Around the World Yacht Race. And the ludicrous part of this leg had been that the local Portuguese boat ran aground—not here, but not much further south, at the entrance to Lisbon.

This time, sailing alone and without GPS or detailed charts, it would have been smarter to stay offshore. But with luck I reached the danger zone at dawn, which brought improving visibility.

The wind became steadier and northerly approaching the latitude of Gibraltar. To ease the downwind sailing for my unreliable wind vane, I launched my secret weapon received just before the start: the Blue Water Runner from Elvstrom.

Fortunately, the head sail furling systems were allowed in this race. The Blue Water Runner is comprised of two identical headsails attached to each other, with a furling in the middle to make shorthanded downwind sailing easy and safe.

The GGR race rules forbade the use of a sock on the spinnaker (irresponsibly, in my view). So I wanted to have something similar to what I had had during my first solo circumnavigation. On that voyage I had hoisted two identical headsails “wing to wing” on the poles without the main to balance the sail plan for my Aries wind vane in the Trades.

But that time I had been sailing a sloop with double forestays and identical headsails with hanks on them. Puffin, as a cutter, had furling on the Genoa and double stays for the stay sails and storm jib, only.

Consequently, I had gotten really excited after my arrival to Hamble Yacht Services (after sailing from New York to the UK). There I had stumbled upon the local Elvstrom sail loft, and I was offered a deal on a highly discounted Blue Water Runner (hereinafter referred to as “BWR”).

The sailmaker himself evaluated this sail as a headsail. In order to comply with the GGR race rules he was going to replace the light, high-tech furling with a traditional and heavy SS (stainless steel) one. He made his measurements on Puffin’s rigging, and promised delivery to France before the start. Well, he kept his word; the BWR arrived on the last day before the start, heavy as hell, and there was no way to test it.

Obviously, I was eager to hoist this sail after my ongoing trouble with the wind vane, hoping for a well-deserved break at the wheel with a balanced sail plan downwind. The BWR premier was a great success; finally Puffin sailed on her own. But my happiness did not last long.

The furling did not move when I wanted to reef in the increasing wind. The upper roller piece and the head of the sails got stuck in the furled-in Genoa because of a lack of clearance (due to inaccurate measurements). Puffin almost overran the sail while I was wrestling it down, bringing me extremely close to a man overboard situation.

The race organizers immediately put this sail on the “No Fly list” as soon as I reported my adventure to them on the mandatory weekly satellite call. Their instruction was completely unnecessary, as the ill-measured furling was not just useless but a danger on Puffin.

I got within sight of Lanzarote (Canary Island) on July 14 (two weeks after the start)—a nice confirmation of my calculations. But I had to put Puffin into heave-to, and put myself into the bunk for a short nap at the NW corner of the island. I was exhausted after the constant and sleepless manual steering.

I reached the first designated GGR checkpoint in the late morning of July 15. There I was warmly welcomed by Don and his team. So in spite of my low remaining energy, I happily posed for their cameras.

To make our farewell heavily loaded, I dropped the protested BWR into their RIB, and kept my doubts of seeing them in Hobart (the next GGR checkpoint) to myself.

But the wind had no emotion as it sped up to 25 knots. It seemed to anchor me to the steering wheel forever as Puffin and I flew along the eastern coastline of Fuerteventura.

As a new development the following day, the wind vane’s pendulum arm tube started to slide out of the pendulum arm while the Northeasterly Trades muscled up to 35 knots, with matching rough seas.

Minor issues on the wheel adaptor were the clumsy clamp levers which were unwanted line catchers (head sail or spi sheets in the cockpit), and had the tendency to chafe the control lines of the main unit.

This time I reached my breaking point—after 19 days of manual steering, irregular eating, little sleep, and the lack of radio communication—and I could not think straight or rationally. I informed Don (as per race protocol) that I was considering replacing my troublemaking wind vane with a Monitor wind vane, and preparing to continue the race in the Chichester class (for skippers who make one stop).

The Almighty might have been evaluating my situation critically, as well, since for the first time I was able to connect with my Hungarian HAM buddy, Tibi Nemeth. In Hungary he had helped me to renew my HAM license, and promised to follow the race with his HAM.

Unfortunately, we were never able to test our communication or make a schedule in advance, due to my other priorities. But he found me in the air now, thanks to French HAM operators who were assisting GGR entrants with WX (weather forecasting). Well, it was a timely boost delivered in my mother language, and a psychological relief to drain my stress to someone else.

So far, I was the only one among the entrants racing without weather reports or a time signal. I was shocked to learn that my chronometer was 37 seconds slow (which can cause significant navigational errors if left unnoticed). So, Tibi’s time signal also came at the best time—sailing Cape Verde-bound, and targeting a place where I could pick up my new wind vane.

I dropped Puffin’s anchor at 3:00am on July 23—after expending all my leftover energy approaching the NW corner of Ilha de Sao Vicente—at the anchorage of a well-protected bay in front of Mindelo Marina.

The designated pickup place for my prospective wind vane was approximately 500 meters ahead of me, but I could think of nothing other than just falling into a deep sleep…

To be continued…