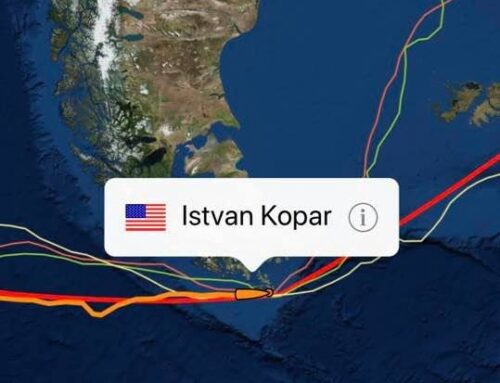

This leg became very long, but its related comments in Puffin’s logbook are extremely brief.

First, the exhausting struggle to stay in the race left neither time nor energy for detailed notes. Second, the frustration caused by the slow progress.

During this time, the logbook contained short, usually one-word references to the weather, the environment, and the current work on board. It rarely stated my physical or mental condition.

On November 21st, for example, “Cold, wet, rough sea, unpleasant sailing. The emergency tiller became useless after a couple of hours. My cursing lasted longer.”

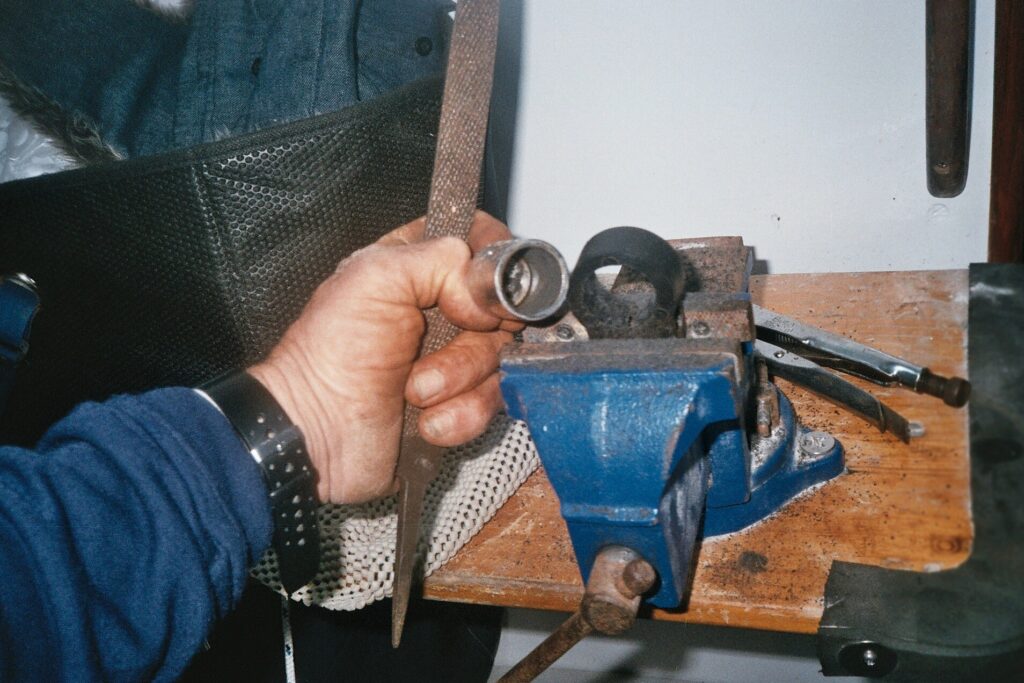

Great design for Emergency Tiller (ET) but poor choice of material (aluminum)

The rudder stock key chew up the aluminum key way within a couple of hours…

Every offshore sailboat with wheel steering has an emergency tiller, an extended part of the rudder stock that can steer the boat during a temporary repair, usually from a snapped steering cable replacement.

Puffin’s original emergency tiller was made of steel, but it was completely corroded by the time she got to me.

I gave the original tiller to my friend Gary in the very early stage of Puffin’s restoration who made all the hardware for the boat during her race prep.

Gary manufactured everything by the highest standards and by my specifications—from the new stainless steel water tank to the very customized chain plates. But we never got a chance to test the new emergency tiller due to ever-changing priorities.

I was very happy with my friend’s new emergency tiller design because it made continuous steering possible without removing the steering wheel.

But a major flaw avoided our attention, unfortunately.

He used aluminum instead of steel to make it lighter and rustproof, which was not compatible with the stainless steel rudder stock, obviously.

I can only blame myself for the mismatch, and the time had arrived to pay the price.

The stainless steel stock wedge chewed up the emergency tiller aluminum groove within hours of steering, making it completely useless.

I slipped on a banana peel.

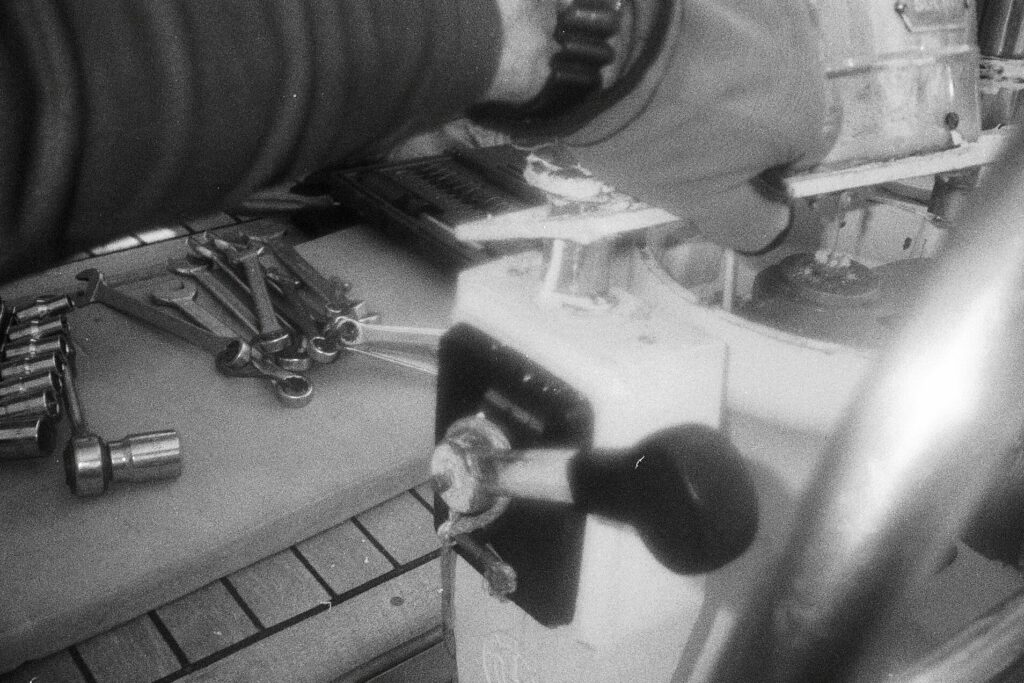

Troubleshoot for steering problems… (2)

The loose bolt is easy fix but the bearing replacement is not…

Worn out bearing needed additional support.

But my endless cursing (as mentioned in the logbook) was not comedic, and my loyal partner, Puffin, pretended to be deaf and waited patiently for my new solution to keep us moving.

Well, it took a while to figure this out, and in the meantime, it called for a customized manual steering solution from the crew (me).

I had to push the wheel forward, towards the bow, while steering. This allowed me to keep the cog wheel and plate engaged inside the pedestal and compensate for the ruined steering shaft bearing.

The “profit” of several thousands of miles of manual steering pays off in situations like this. Every muscle of the helmsman naturally matches the rhythm of the sea, changes in the wind, and the motion of the waves. All unconsciously, to keep the desired heading.

Yes, my body was stuck at the wheel for a long time but not my mind.

My eyes constantly scanned the visible boat parts, and my brain, the invisible inventory on board looking for the material suitable for bearing fabrication.

Finally, my choice was the end fitting of the wind generator’s supporting tube, which by its matching dimensions, looked to be a good fit for the bearing replacement.

The outside diameter of the Stainless steel supporting tube was identical to the diameter of the steering wheel shaft by lucky coincidence.

My competitive spirit urged me to keep helming Puffin. While in my head, I created the blueprint of replacing the end fitting with something else and the step-by-step bearing manufacturing process in advance.

The goal was to reduce the time both for the fabrication and the “heave to” idling while Puffin is in shackles—again.

The first step was to secure the wind generator when I removed the end fitting. The second step was to modify the fitting for a completely different function. Finally, I had to install the make-up bearing to a place where it could be effective.

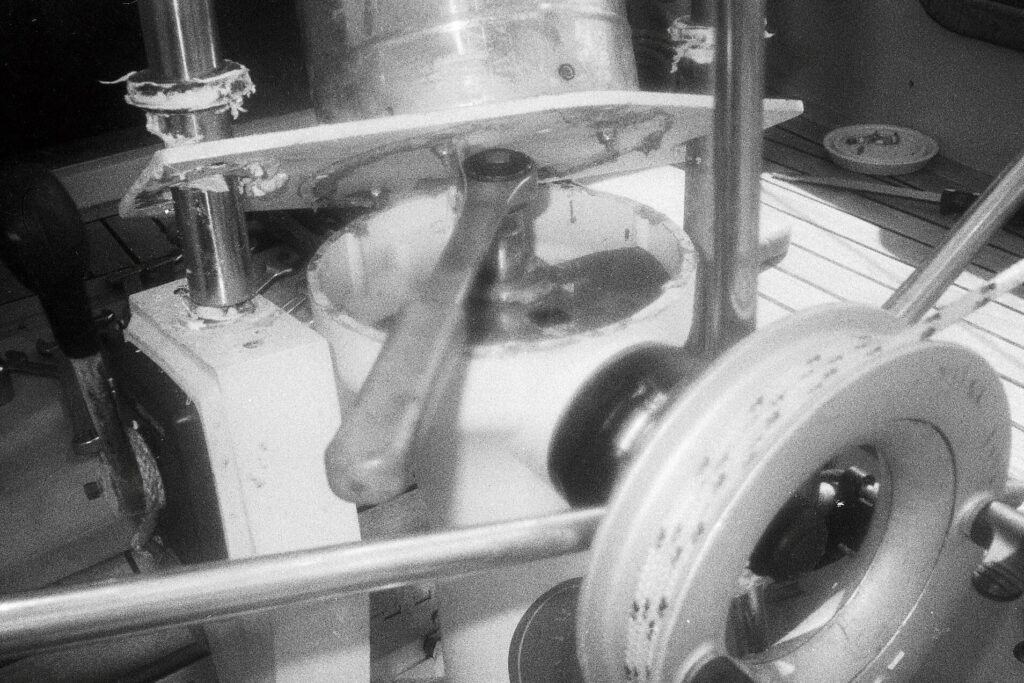

I removed the eye end from the Windgenerator’s supporting pipe to make a bearing of it

This wise- a gift from a friend Colin Buffin-was constantly in use during the race…

my home made bearing has even a lubrication hole on it.

The original wheel locker became a bearing locker this time

I glued the modified eye end into the wheel locker housing.

The modified eye end works as a bearing now

Whitlock Cobra 4 or 5 rod steering is not compatible with Windpilot

The most suitable spot for the latest looked like the steering wheel lock itself. Its original purpose was to lock the wheel while Puffin was on anchor or mooring, and none of these actions were on our horizon, for sure.

The execution of the well-planned job did not go without glitches.

The major distraction was maintaining Puffin’s status within the racing rules while I was fixing her steering, in this case, staying out of the “No go zone.”

The purpose of the prohibited area was to enhance the safety of the competitors (not letting them sail into the higher latitudes). But this restriction proved to be everything but safe in our case.

Staying in the permitted lower latitudes resulted in a lot of frustration due to the ever-changing weather and sea conditions. Long-lasting windless periods alternated with shorter storms, negatively impacting Puffin’s progress and her crew’s physical and mental health.

I had to reef the sails even in the wind holes just to reduce chafing on the rig and sails.

On November 27th, I almost had a very bad ending while I tried to replace the snapped main halyard. I spent 2 hours on the mast top and could barely crawl back to my bunk to recover.

The safety zone became hell on water due to the slow progress. The constant rolling and pitching eroded both Puffin’s and my condition. Moreover, it lowered the chance of collecting sufficient drinking water.

In December, I escaped into another challenging project to save our soul and seaworthiness.

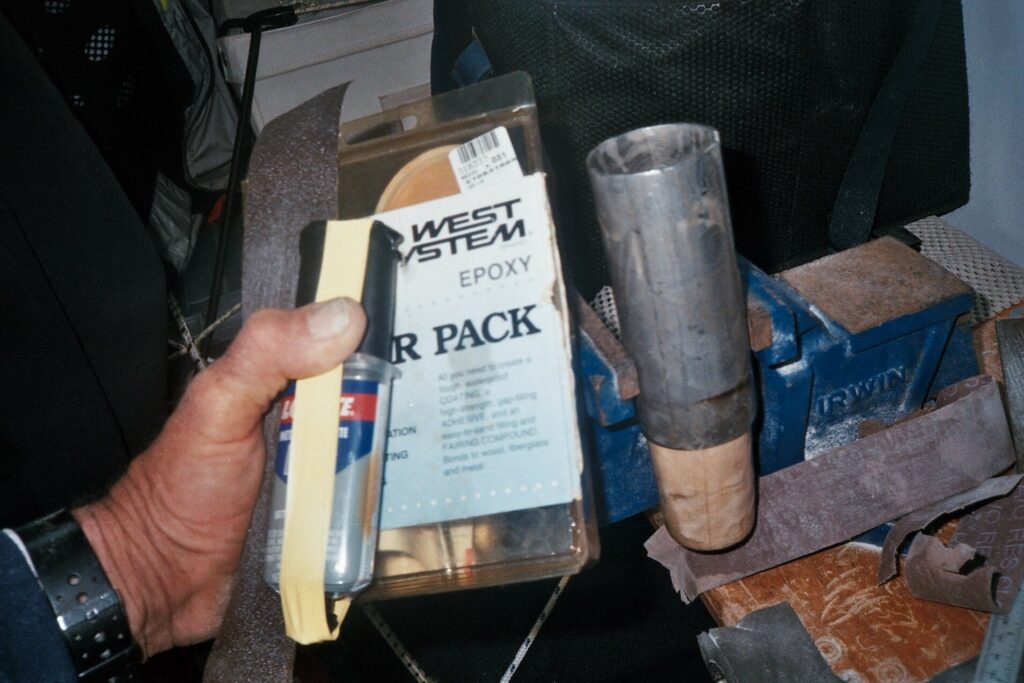

I had to fix the emergency tiller as the finish line was still several thousand miles away.

Thanks to my heavy but limited inventory, I found a 6” long stainless steel pipe, and its diameter was a good match for the aluminum emergency tiller.

It was easy to cut the groove for the rudder stock’s wedge, but to bond this piece to the aluminum emergency tiller was a different question.

First, I made a wood insert, a filed down a wooden bung (leak stopper), and glued it with epoxy into both, arming the aluminum emergency tiller with a stainless steel head. Then, I drilled a drain hole above the wood insert and injected water into the tube with a syringe.

It sounds ridiculous now, but I tried to catch every glimpse of possibility in that situation and hoped that the swelled wood would bond the two pieces together…

But, unfortunately, the wood insert sheared away after a couple of hours of trial.

Cutting the new key way was easy...

when the sea bung gets a new function

1st attempt to connect a SS head to the aluminum ET.

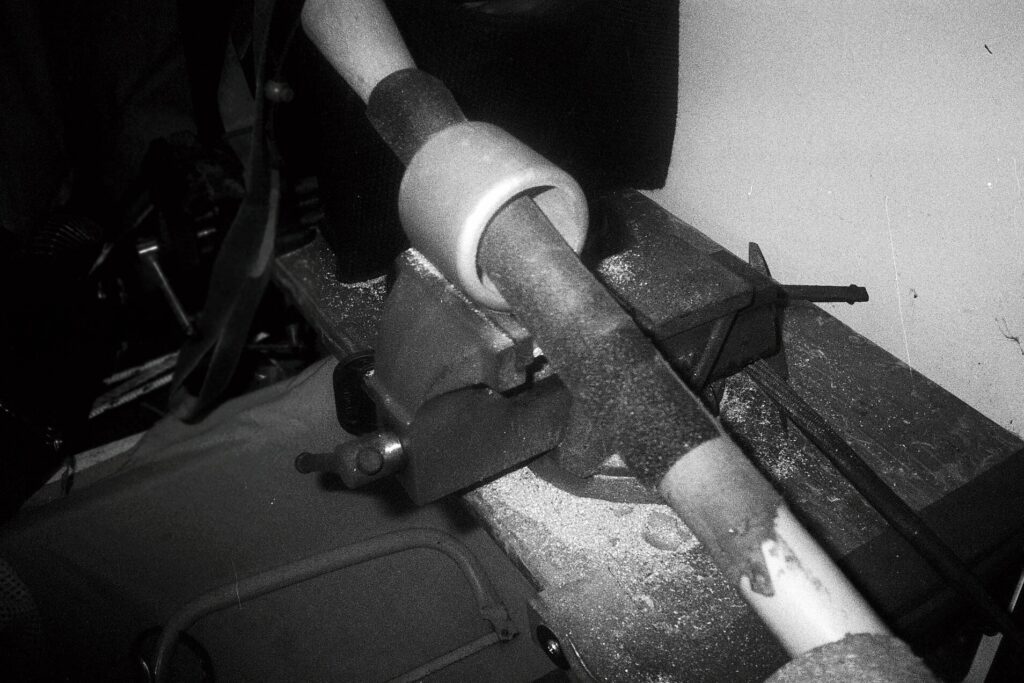

In my next move, I filtered through the parts of the spare Windpilot and found a cast aluminum flange, a prospective collar to connect the two pieces together.

After eight hours of non-stop filing using a 2’ long aluminum pipe with self-adhesive sanding paper as a handmade circular file, I slid this piece onto the Stainless steel and the aluminum tubes.

I “welded” the stainless steel and aluminum tubes together and reinforced them with stainless steel through bolts.

This would qualify as butchering in a machine shop, but I steered with this emergency tiller 1500 nm for the rest of the race.

This Windpilot spare part became a connecting sleeve...

This sleeve has to go on!

Home-made file was in action for 8 hours...

Finally, it’s on…

On December 4th, Puffin lost her Davis wind vane (wind indicator) from the masthead in a 65 knots blow which was escorted by heavy hail to invite me for a drink. And the following night exposed further damage; there was no operable masthead light either.

But these losses were insignificant compared to Susie’s loss. She lost her mast completely and her boat, too, a few days later.

On December 9th, a bulk carrier crossed our way, interrupting our isolation and confirming our position at 45-44.8 S and 132-17.4 W coordinates.

On December 12th, we got the green light, finally. We were able to turn towards the higher latitudes and leave the trap of the safety zone behind. These days were pretty foggy, reducing the navigation to dead reckoning.

On December 16th, we got visitors. An Orca family was curious about us—or they just wanted to alert us of a new approaching storm. The following days were cold, but they brought life-saving rain, and I collected 30 liters of drinking water.

Potential drinking water on the horizon….

The drinking water inlet…

Drinking water outlet

Happy hours, let's have a drink...

Interestingly enough, my propane tanks had a double function. They worked as storm sensors, running empty during the storms, only making their replacement more exciting.

On December 22nd, a bone-biting cold storm decorated our surroundings with hail and snow.

On December 24th, inside the cabin, the thermometer showed 4 C outside, and the sea was furious. It would have been more than cynical to sing the Holy Night…

But the last week of the year turned into April—not by its temperature but its unpredictability. Storms alternated with wind holes daily.

I got really drunk on the last day of the year. It was the first time I could drink without limits, as I collected 50 liters of drinking water from the mainsail.

2019 started very well for us. Puffin (for her first time) and her skipper (for his second time) rounded the ill-famed Cape Horn.

To be continued…