Puffin left Bermuda on May 7 at 08.30 in an 18- to 22-knot southerly breeze. I could expect a real solo ocean crossing in splendid isolation due to my inoperative satellite phone and HF radio. However, my navigation was supported by the B&G Chart Plotter still onboard (which wasn’t removed until in France just before the race start), and it gave me the opportunity to compare my celestial calculations via sextant and chronometer. Well, I could not brag about the initial results, as the 3-decade-long break without practice was just too long. The Echomax Radar Transponder (a GGR requirement) was the other aid in my singlehanded sailing, since it alerted me about nearby vessels well in advance.

The weather was pleasant for a couple of days, making showering in the cockpit possible. But I lost this tiny comfort before long, due to cooler air and increased waves as Puffin progressed towards higher latitudes.

Puffin’s original sails were in great shape despite their age, but were undersized for the new, taller Selden rig. The cutter sail layout, including the Yankee, was new to me. But I started to appreciate its advantage with the worsening weather, and faulted myself for skipping the Yankee in my English sail order.

The only stressful period of the 3000nm-long crossing was the finish, sailing in the English Channel in fog with increased shipping traffic and currents. By the end of May, my ETA to Solent had slipped to June 1—and for the approaching low tide, unfortunately. As I was crawling at 1-1.5 knots towards my final destination, I recalled my previous Solent approach in 1997 with nostalgia. At that time, as the skipper of the leading boat (Tripp 55’) in the Hong Kong Challenge Around the World race, I had arrived here with the coming high tide (at the same time), making our finish to Cowes easy.

But Hamble was my destination this time, more precisely Hamble Yacht Services, where I was invited as a guest thanks to my English friend Bertie Bicket. HYS is the ideal marina for an offshore sailor because the quality marine professionals and shops are all within arm’s reach. And I needed them, as the ocean crossing—Puffin’s first serious sea trial—had created a long “to-do list.”

The top item on my priority list was the wind vane, since its reliability would play a big role in our special race. My wind vane had dropped the course several times since Bermuda. I hoped that the problem was installation related, so I contacted Peter, the designer and manufacturer of Windpilot, for help. He was just too busy with his business in Hamburg, but promised his help before the race start in France. No one within range of Hamble was familiar with Windpilot, so I had to postpone the solution of this issue, unfortunately.

But I was not short on other tasks, and I would have been in big trouble if divine intervention had not directed Peter Orban to Puffin. The sailor of Hungarian origin had his sailboat moored in a nearby marina, and he volunteered his help for 2 weeks, at the expense of his own work.

We hauled out Puffin for bottom inspection, checking her Seahawk antifouling and replacing prop zinc. We tested Peter Sanders’ new sails, with great appreciation for the quality of his work and his professional attitude. We also added new hand holds to the interior. And we filtered through my overstocked tools and spares, working to streamline the inventory.

We added local freeze-dried food to my provisioning, and called for professional help for the satellite phone and HF radio problems. And as usual in boat repair, we just opened a new can of worms, finding Puffin’s house batteries were cooked due to overcharging. The battery storage was custom-made, and the batteries that fit were only available in the U.S. Their order and shipping was another unexpected drain, both on my wallet and my schedule.

Another discrepancy was found on the port upper spreader, which had somehow changed its desired angle, and the inner end had gotten slightly damaged. The rig got retuned, but the spreader replacement had to be postponed until France.

We got some breaks during our nonstop work thanks to the visitors, and not even they came empty-handed. Adam and Erika, my friends from London, picked up Puffin’s repaired sails from Peter Sanders’ shop (in Lymington) on their way. Another friend, Csaba Horvath, swung by in a charter boat with half a dozen Hungarian sailors onboard, and surprised me with some drink and timely cash.

Ten days flew by with the speed of seconds, and the rising sun found Puffin, Peter, and me in Falmouth on June 11. We docked in the crowded marina among the other GGR boats, some of us rafted despite the fleet number having whittled down to only 17. We greeted our prospective contenders with pleasure, and tried to measure up their boats as we were just laying eyes on them for the first time.

The schedule of the following three days was loaded, dictated by the race management and local authorities. Sir Robin had wisely chosen Falmouth as his departure and arrival port in the original Golden Globe Race 50 years earlier (June 14, 1968). He was the only finisher, and consequently the winner of the race. With its meeting here, the GGR fleet wanted to express our admiration towards the legendary sailor and honor his support in our current race. It was a “win-win” situation: we joined the local anniversary events, and Sir Robin promoted our race with his presence in the related events and accumulating media. He docked his world-famous circumnavigator boat Suhaili next to our fleet on June 12, connecting the past and present symbolically, too.

Our skipper meeting on the same day was lengthy and exhausting. Among other things, we received our pricy medical container, which cost 1500 English Pounds (almost $2000 USD). We also learned about its contents and how to use them. Our doctor was an experienced professional in medical care at sea, and gifted with a good sense of humor, but he was not 100% ready for the special features of our race. He referred frequently to how we could help each other in the case of a medical emergency, assuming that we would be sailing within reach of each other during the 8- to 10-monthlong race.

I could not neglect my sponsors either while following the mandatory program, so I used the breaks for interviews and reports. WEMPE, one of my main sponsors, sent a photographer to Falmouth—besides their financial support and lending me their beautiful merchant marine chronometer for the race. Their photographer hijacked me from Puffin and made me pose on the beach like a model.

A lonely circumnavigation started to be more attractive by the day after this madness on the land.

The friends are always exceptions, of course. I was delighted to see Colin & Sue Buffin had arrived from New York to wave farewell. And Ian, my team manager, also flew from there to sail with me to France.

On June 13 the Royal Cornwall Yacht Club invited us for dinner and regaled us with fireworks, perhaps with some regret that Falmouth had rejected hosting our race.

Well, the sympathy should be on the side of the GGR entrants and organizers, since besides the race prep we had to fight for the existence and execution of the race ourselves. In 2015 we gathered in London, planning with Falmouth as the prospective host of GGR 2018. Later Plymouth jumped in, because the race founder Don and his enthusiastic team were faced with the same difficulties as the provisional entrants.

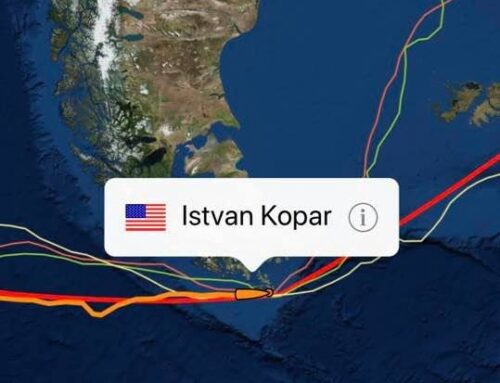

Offshore sailing and sailing in general have gotten a wedge dividing the sport and its fans between the traditional displacement boats and the new hydrofoiling “go fast” boats produced by the technological progress of the modern era. The younger generation especially are far more attracted to the latest ones that can foil upon the surface of the water. Their offshore versions are equipped with high-tech navigational and communications systems, looking more like space shuttles than sailboats. Their production and operation are very expensive, but the money attracts the professionals both in business and media. Solo circumnavigation is now possible within 42 days with these “speedboats,” and thanks to the satellite tech it can be followed visually.

Our race, in contrast, besides representing traditional sailing, is focused on the sailor—not on the land-based manufacturing and teamwork. The GGR’s mission is to promote self-supportive sailing, challenging the contenders within the era of 1968.

Sponsors, the media, and even part of the sailing sport community considered our lengthy ocean marathon an unworthy event that could not be followed visually, since even the photo/film recording would be old-fashioned (as per the original official GGR Sailing Instructions).

The English let us go (dropped us), and without a race sponsor or host, even the execution of the race itself became doubtful. Luckily one of our French contenders, the veteran circumnavigator Jean-Luc Van Den Heede—the well-known resident of Les Sables-d’Olonne—saved the race, with the help of Yannick Moreau (the host of the Vendée Globe).

Consequently, we had our next mandatory meeting (December 2017) in LSDO and at the Paris Boat Show, causing an extra detour both financially and timewise for the entrants from remote places. But solo circumnavigation and shorthanded offshore sailing in general have a different status in France than anywhere else in the world. The Anglo-Saxon spotlight is usually on the team sports, while the French rather appreciate and honor individual performance. The ocean solo sailors are famous national heroes to them, and media attention and financial support have been matched accordingly. The hunt for sponsors in the U.S. for instance is hopeless, while it’s common practice in France.

However, bureaucracy has no borders, and the French sailing one was no exception, considering our original GGR race concept ill-prepared and unprofessional. Don, the GGR race founder, had no choice—he had to adopt the tools and requirements of the current races in the field of safety and rescue measures. This made our to-do list longer, and our shopping list more expensive.

Luckily the scheduled Falmouth-LSDO pre-race had a “warm-up” function, aimed only at charity and the testing of our communication systems. The main goal of Ian and I was to get to France as soon as possible so we would have enough time to complete our safety list and pass the boat inspection. In short: qualify for the “green card” as an official race competitor before July 1.

June 14, 2018—the 50th Anniversary date—started with a sailboat parade at 10am. The weather gifted us with a fresh breeze and plenty of sunshine as the celebrating fleet sailed around in Falmouth’s beautiful bay. Then the fleet, led by Suhaili under Sir Robin’s command, headed out towards the starting line in the open water. Suhaili was followed by classic boats and finally by the GGR competitors, with the fleet of visitor boats loaded with fans.

The start gun was shot on board Gypsy Moth IV at 13.30, and the participants in spectacular formation crossed the starting line of the 400nm-long “SITRan” Charity Race.

To be continued…

I visited to Falmouth to see the boats and the exciting premain event rather than to visit to LSDO.

I enjoyed in walking along the coastal trails and watching the beautiful scenery of Falmouth.

After seeing the yachts sailing far from the start line from the tip hill in front of Pendennis Castle

I took the train to Plymouth for travellng around the port city.