A seemingly unattainable dream was put into words in my childhood: to sail around the globe solo. With

only one stop. And in only one year.

How could I even think of such a venture—being a citizen with limited means and of a country without

sea borders? There was a lack of shipbuilding industry, experts, and respective supporters.

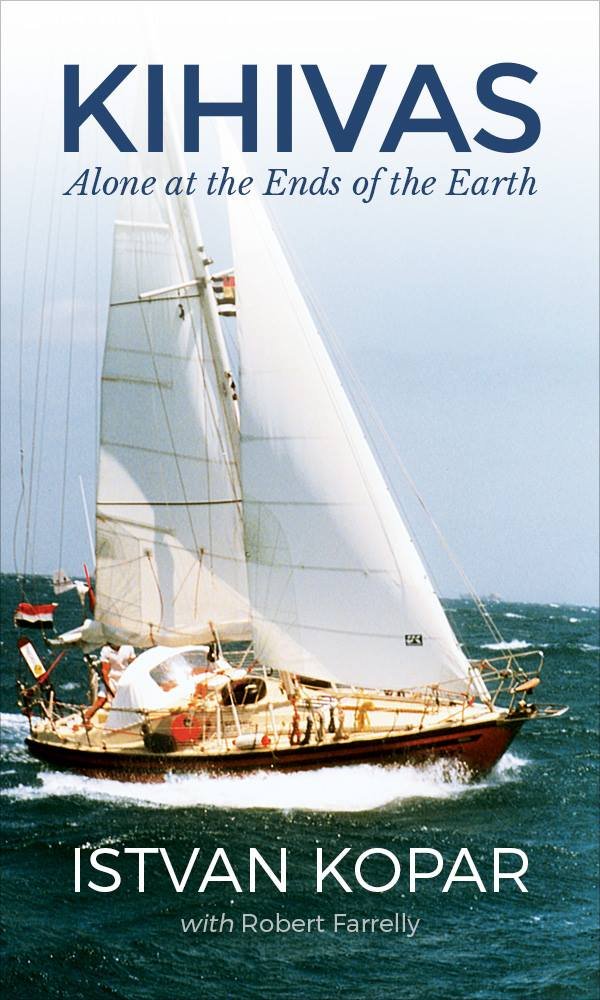

Yet, in just two years, and at the price of great efforts and sacrifice, my friends and I built the strongest

Balaton 31.

She was named Salammbo after Hannibal’s sister.

And, after the traditional christening, Salammbo rolled to Pula on the Adriatic Sea on a giant trailer.

The boat was ready to go, but the 34-thousand nautical mile, one-year voyage demanded well-planned

provisioning. I needed a good supply of spare parts, tools, and endless necessary items.

I cast off on June 16th, 1990.

Francis Chichester, an Englishman, was the first to bring the idea down to Earth, proving himself worthy

of the knighthood conferred upon him by Elizabeth II upon his return.

Undoubtedly one of the greatest and most memorable figures of sailing, Chichester faced extraordinary

trials despite launching his yacht from England, the citadel of sailing, and being backed by numerous

advantageous fundamentals.

The route to Gibraltar, the actual launching point, crossed the Mediterranean.

Sailing and a love of water are not just a recreation or hobby but my chosen vocation.

My childhood and youth yacht racing adventures were enriched by my 15 years of experience as a

merchant mariner in Hungarian commercial shipping.

The preparations for my great journey began in my early childhood. Having grown up as a skilled lake

sailor and qualified naval officer, I eagerly awaited the fulfillment of my dream as a professional.

However, I couldn’t afford a real blue water boat capable of high speed and suitable for single-handed

sailing. Instead, I had to make do with an outdated 31-foot boat adapted for near-coastal sailing but

essentially designed for Lake Balaton in Hungary.

This meant replacing and repairing equipment, endless fitting adjustments, and packing essential items

like clothing, medicine, books, and thousands of other necessities. Finally, the preparations were

complete, and I was ready to make it until my single port of call in Perth, Western Australia.

I had to load 580 kilograms of preserved or canned food and 600 liters of water into Salammbo, a boat

the size of a maritime lifeboat.

Gibraltar, the countdown began.

These were the final preparations for the boat, as the scheduled landing was still 4-5 months away.

The 28th of July 1990 was the day of departure of sailing, and would there be an arrival?

There are numerous ways to sail around the Earth, for example, via the Suez and Panama Canals in the

slightly risky Equatorial and Trade Wind zones. The number of stops, the direction of circumnavigation,

the size of the boat, and its equipment are all significant factors that make an exact, comparative

evaluation of a circumnavigation nearly impossible at first glance.

The very first solo circumnavigator of the world, the Canadian-born Joshua Slocum, under the US flag,

ended his three-year-long cruise around the globe in 1898, and the number of solo sailors did not go

beyond a hundred during the last century.

In the beginning, I hoped to rank among the top ten recorded achievements, considering the size of the

boat, its equipment, daily progress, the nature of the route, and the number of stops. However, an

unexpected event enabled me to achieve an even better result.

Namely, the year 1990/91 was the year of the maximum sunspot cycle, occurring every eleven years.

This event had a cyclone-animating effect that inspired my otherwise sluggish Salammbo to sail at

speeds far beyond what was expected. Thanks to this boost, my boat was able to reach a speed record in

its category with a daily average of 125 nautical miles, steered only by manual and wind vane.

When selecting a route, I chose to sail via the five southernmost capes of the continents, which

according to nautical literature, is one of the most challenging sailing routes. Starting from the southern

coast, I sailed around the Cape of Good Hope in Africa, Cape Leeuwin in Australia, the southeastern Cape

in Tasmania, the southwestern Cape in New Zealand, and finally, the dreaded Cape Horn in South

America.

I sailed across the Indian and Pacific oceans between the ill-famed Southern Latitudes of the 40 and 60,

where the Roaring Forties, Screaming Fifties, and Furious Sixties are famous for their high winds and

mountainous waves and even for drifting icebergs and poor visibility.

Beyond the modest technical equipment, the slowness of the boat resulting from her design and size

meant the greatest problem because I could not time these critical stages for the optimal period, the

southern summer.

Salammbo endured the raging winds of the South Atlantic and the Indian Ocean, including winds of

120/140 km/h and waves as high as 14-16 meters during the late southern winter. And thanks to God,

the only capsize was in the Indian Ocean, which meant endurable damages.

The remarkable feature of the voyage’s first leg to Australia was that Salammbo (without any previous

sea trials except sailing from the Adriatic Sea to Gibraltar) reached the coast of Australia with hardly any

interruptions despite the endless storms. During this stage, I did not see land, ships, or human beings for

three and a half months. However, solitude did not trouble me.

My frail technical equipment, regularly out of order, helped me because I had to lean on traditional

celestial navigation, thus passing most of my day. My shortwave radio, however, proved reliable so my

friends’ ethereal presence also helped to fight the feeling of loneliness.

After sailing for four months and one day, I embarked—almost on schedule—in Fremantle, Western

Australia.

The hospitality and friendly assistance of the sailors in Success Harbor brought me unspeakable

happiness.

The first true Christmas present was the arrival of my family in Australia.

My daughter, Piroska, conducted an improvised interview with Chris Mews, the Harbor Master, in which

she asked about the hardships of my journey. As a skilled sailor with experience in the Sydney-Hobart

race, he emphasized the extraordinary nature of my venture and sincerely believed in its

accomplishment.

Perth is Western Australia’s beautiful capital, and Fremantle is its sea harbor.

I had to rapidly prepare Salammbo for the second—possibly more dangerous but obviously longer—leg. I

worked 10-12 hours daily for four weeks so my boat could sail off filled with supplies on her way home.

My ever-joking Australian friend, Peter Fletcher, amused us during the breaks with his improvised

commercials.

Success Harbor is a famous port of call for the world’s wanderers. We wished bon-voyage to Michel Jan,

the French pilot, at the departure for his long ocean journey.

Besides doing the necessary bottom job (antifouling treatment) and lengthy repairs, I had to replace my

food and water supply.

On December 29th, 1990, I said goodbye to my new friends, uncertain whether I would ever see them

again, and set off towards my exciting new adventure: the vast Southern Pacific Ocean.

Although the most dreaded Cape, Cape Horn, and the vast image of the ocean weighed heavily in my

mind, the routine of the several thousand miles sailed so far prepared me for what was to come.

The freezing cold, salty moisture, iceberg dangers, constant ups and downs of the waves, and bland

preserved food all became natural parts of my days. As time went on, I found myself identifying more

and more with the unexplainable life of the albatrosses and even took pleasure in it.

I realized that despite the Southern oceans’ severe and extremely hard conditions, it is a wonderful

world that lacks all malice and rewards the survivors with an unlimited feeling of freedom.

My scale of values, my world conception changed, the ambitions of the consuming society seemed

ridiculous. I learned to rejoice in the present, including the tiny details.

It was pure happiness when after three soups landing on the ceiling, the fourth finally reached my

stomach. If I survived the rough passages, if I breathed in my ever-damp sleeping bag, if after several

days of hunting I could measure a celestial body, if I could have an overall bath in two liters of water, if I

could take a good book in my hand,or, if I could rarely meet a ship.

The dance of the always present, unwearying dolphins, the joyful jump-abouts of the paddling seals in

the stern wake of my boat, the body language of the albatrosses following me for days, the radiant

benevolence of the majestically moving whales interpreted the existence of an unspoiled but rapidly

shrinking paradise even among th e most miserable conditions.

After almost two months of lonely sailing, in the latitude of 59 degrees 26 minutes South and in the

longitude of 101 degrees 45 minutes West, I met Nandor Fa skippering Alba Regia, as the Hungarian

participant in the BOC circumnavigation race.

It might not be an exaggeration to consider this irregular meeting an event of sports history. Hopefully,

the ladies will not take offense if I say I have never rejoiced so much in a rendezvous.

Meeting with Cape Horn was not a long way off either, although there were moments that I would have

gladly renounced.

Naturally, no photos could be taken of those moments since at these times—as in all perilous

situations—the cameraman was prosaically fighting for his life.

With the passing of months, not only the miles waiting for Salammbo decreased, but I was also

desperately running out of supplies, so I welcomed the scorching sunshine of the tropics, getting used to

the rigid diet of modern nutrition.

A never-ever experienced before how the silence leans on the ocean, peace, and tranquility settle in air,

water, matter, and mind.

As the boat headed further and further North, more and more constellations visible from home

appeared.

Taurus and Carter rose higher and higher. The Cross of South and Centaur lowered day by day.

Should I be happy, or should I be grieved?

On starry nights the lack of family, friends, homeland, and homesickness threatened to overtake, but at

the same time, my instincts seemed to suggest: why hasten the time? Why hurry out of paradise?

This is a windless period, pecked with gentle breezes. I only met something similar on the

Mediterranean.

I should long be in the Southeastern trade wind!

I blame civilization, specifically the nuclear reactors, our computerized robot world, and Saddam Hussein

at the same time. If such balanced winds become inconsistent, the trouble must be enormous.

But fortunately, the calms were not everlasting.

The sea became more and more polluted—signaling the approaching of Europe—and the moment so

many times only dreamt of, came true.

In the morning, I sailed into the harbor of Gibraltar.

With four months and 17 days of sailing with no stop in the second leg, I beat my own record set during

the voyage’s first leg.

Pula is only a few weeks from Gibraltar, the port I last saw a year ago.

To release the energy accumulated during the ocean marathon, I sailed across the Mediterranean under

ideal conditions.

And although many things changed during my absence, those who were waiting for me, and their

feelings were nearly the same.

I arrived. I did it!

With this, a long journey and an extraordinary venture ended.

Salammbo’s circumnavigation was a real challenge—a human and professional trial. I had an

overwhelming desire to see clearly, to know my capabilities and my worth. In terms of difficulty, the

planned route seemed suitable for this purpose.

I realize that my perspective may seem selfish and overly personal, and to some extent, it is. However,

Salammbo sailed under the Hungarian flag, and both departed from and returned to Hungary, earning

her a place in the history of offshore sailing. In this sense, it represented a message to the world and to

our fellow compatriots.

Proving that there is no impossible with the required preparations, persistence, and despite unfavorable

fundamentals. Faith in this restores one’s confidence and might inspire action.